REUTERS/Manon Cruz

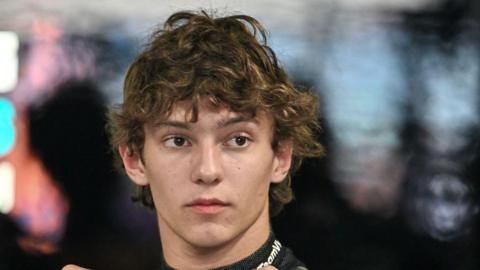

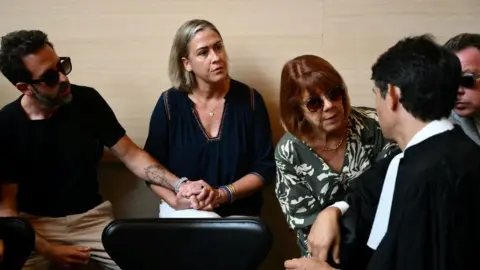

REUTERS/Manon CruzWhen she walks into the courthouse in the French city of Avignon, flanked by her children and a team of lawyers, Gisèle Pelicot cuts an unassuming figure.

The 72-year-old mother and grandmother, her hair styled into a neat bob, wears colourful dresses and Breton tops. She looks down as she passes the dozens of journalists gathered by the entrance, her eyes hidden by round-framed sunglasses.

Behind them, as she has put it, lies a “field of ruins”.

Nearly every day since 2 September, Gisèle Pelicot has been at the centre of a trial in which 51 men are accused of raping her, including the man she was married to for 50 years.

As her story has rippled through France since the trial began, she has become a symbol of courage and resilience.

“I was sacrificed on the altar of vice,” she said, explaining how she had learned that Dominique Pelicot had drugged her to sleep and recruited men to treat her “like a rag doll” for over 10 years.

The trial, due to run until December, has so far heard evidence from lawyers, police, psychiatrists, and from another woman whose husband drugged and raped her following instructions by Dominique.

CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFP

CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFPThe Pelicots’ daughter, Caroline, who believes her father abused her when she was unconscious, has also taken the stand.

Dominique Pelicot has admitted the charges against him, although he denies abusing his daughter.

Unsettling details of the defendants’ pasts, psyches and alleged crimes have filled the airwaves, news websites and social networks.

This kind of access has only become possible because Gisèle has waived her right to anonymity.

In a case of such magnitude it is an unusual decision, not least because it means thousands of videos of the alleged rapes filmed by Dominique Pelicot – in some cases surreptitiously – will eventually be played in open court.

Gisèle’s only request was that her children be allowed to leave the room when that happens.

Christophe SIMON / AFP

Christophe SIMON / AFPHer legal team said opening up the trial would shift the “shame” back on to the accused.

Above all, the case has ignited a painful – and often uncomfortable – discussion about rape that many in France say is long overdue.

Protests are due to be held across the country on Saturday “in support of Gisèle Pelicot and of all rape victims”.

When Gisèle gave evidence that she had to “start over from scratch” and was now only living off a small pension, an influencer set up an online collection that made €40,000 (£33,700) in under a day. It was quickly shut down following a request from Gisèle’s legal team, who saw it as a possible distraction.

One key issue this case has thrown up is the little-discussed phenomenon of chemical submission – drug-induced assault in the home.

In 2022, 1,229 people in France suspected they had been drugged without their knowledge, according to Leila Chaouachi, a pharmacist at the Paris addiction monitoring centre and an expert on drug rape.

That number is probably “only the tip of the iceberg”, she believes. Victims often hesitate to file legal complaints because they know the assailant, they might be ashamed, or they have hazy memories of what happened.

Complaints also need to be filed before the substances disappear from the body, which is not always possible.

For the 10 years her husband was drugging her, Gisèle Pelicot had unexplained neurological symptoms as well as gynaecological issues, and yet no-one put the clues together.

It points to a lack of awareness of chemical submission as a phenomenon.

Dr Chaouachi says training healthcare professionals and police is important, because the key to stemming the issue lies in recognising that there are others out there besides Gisèle.

“We have the right to be shocked, but we also need to recognise that these aren’t isolated cases,” she says.

“When we only focus on the justice system and investigators, we’re hiding behind them in some way. I think it’s a broader societal issue, and therefore it’s societal change that we need.”

Judging from opinions voiced on the streets of Paris, that view is not universally accepted.

Christophe SIMON/AFP

Christophe SIMON/AFP“It’s a private affair,” said one man, who thought the case was awful but still an isolated event and not one for public debate.

“I don’t understand why the media are making such a big deal about it. It is because people like drama, gossip.”

A friend agreed: “If you hadn’t asked the question, we would’ve never discussed this.”

But a female companion said they were both wrong: “It’s important this case is public… it raises a broader issue and raising awareness of it is necessary for change.”

What has shocked so many in France is the sheer number of men involved in the case.

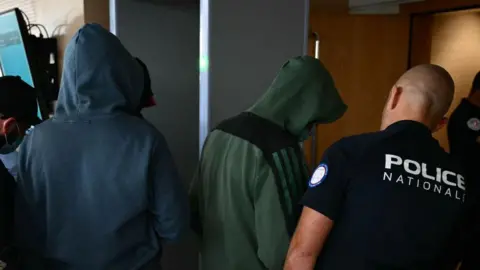

Police were only able to identify 50 suspects out of the 83 that appeared in Dominique Pelicot’s videos.

Their ages range from 26 to 68 and they hail from all walks of life – firefighters, pharmacists, labourers and journalists. Many are fathers and husbands.

Of the other men accused, 15 admit rape, but all the others admit only to taking part in sexual acts.

“What shocked me even more is that so many men could have done this – more than 50 ‘normal’ men, who all lived nearby,” said Caroline, a 43-year-old doctor from Paris.

“[Pelicot] didn’t even have to look very far for them. It really scares me because it is a reflection of society. It’s not the norm, but there are too many.”

Céline Piques of feminist organisation Osez le Féminisme hopes the fact that the accused come from ordinary backgrounds and all kinds of professions will mean that this trial has a lasting impact.

“It demolishes the myth of the rapist who is a psychopath… they raped because they were sure of their impunity.”

Another concern that has not escaped the large numbers of women across France who are following the Pelicot case is that many other men knew and did nothing.

Dominique Pelicot had invited men to have sex with his wife “without her knowledge” in a post on the Coco.gg website, which was shut down only last June. Last year it counted 500,000 visitors a month.

“One hundred per cent of these people… never made a phone call to stop this abuse,” says Céline Piques. “Not one man thought about informing the police of these criminal facts.”

The Avignon trial is also dredging up questions over the language surrounding rape.

The defence of many of the accused hinges on the premise they did not “know” they were raping Gisèle – in other words, that they thought they were having consensual intercourse with her.

Some have accused Dominique Pelicot of “manipulating” them into believing they were taking part in an erotic game in which Gisèle was only pretending to be asleep because she was shy.

At least two of the defendants stated they did not feel they had raped Gisèle because she had been “offered” to them by her own husband, and one man said he did not consider his actions rape because “for me, rape is when you grab someone off the street”.

“I don’t have the heart of a rapist,” he added.

REUTERS/Manon Cruz

REUTERS/Manon CruzSumming up this line of defence earlier this week, Guillaume De Palma, a lawyer for six of the defendants, caused outrage when he said that “rape is not always rape”, and argued that “without the intention of committing rape, there is no rape”.

In French law, rape is sexual penetration obtained by constraint, violence or surprise – and Gisèle Pelicot’s lawyers are expected to argue that “surprise” covers the case of a sedated or unconscious woman.

But the comments caused outrage and dismay in the courtroom and beyond.

Gisèle’s daughter Caroline stormed out of the trial exclaiming “I am ashamed of the justice system”, while the president of the court suspended the session amid a mood that reporters described as “extremely tense”.

Other lawyers reportedly distanced themselves from De Palma’s comments.

With the trial due to run for three more months, France’s soul searching will continue.

“It has shown how far behind we are at all levels,” said Sandrine Josso, an MP who was the victim of an attempted drug rape by a senator in 2023.

Thanks to Gisèle Pelicot, she said “we lift the veil, and we discover a lot of things”.

The ordinary nature of the couple at the centre of the trial – middle-class pensioners and grandparents – has made it easy for observers to identify with the story.

“I thought it could be my mother, my sister… and my father,” said Charley, a 35-year-old man living in Paris.

“For me, it’s the trial of the century,” he added.

“There will be a before – and there will be an after.”

Additional reporting by Eva Van Dam