Reuters

ReutersWomen working in hospitals in Pakistan say they regularly face sexual harassment, violence and verbal abuse, from male colleagues, patients and their families.

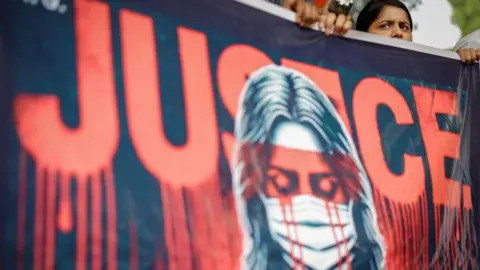

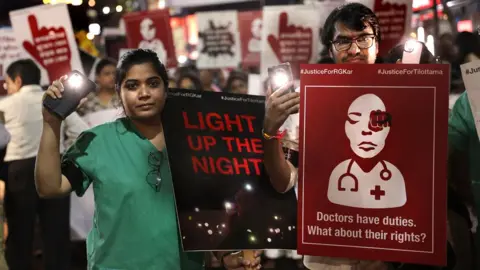

Following the rape and murder of a 31-year-old trainee doctor at work in an Indian hospital, more than a dozen female medics in Pakistan told the BBC they were worried about their own safety.

But this is a largely hidden crisis, as many are too scared to come forward to report the crimes – while those who do are often told no one would believe their allegations.

Most of the women the BBC spoke to asked that their names be withheld for fear of losing their jobs, “honour and respect”.

A few months ago, a young doctor came to Dr Nusrat (not her real name) in tears. While she was using the toilet, a male doctor had filmed the woman through a hole in the wall and was using the video to blackmail her.

“I suggested filing a complaint with the FIA [Federal Investigation Agency, which handles cyber crimes], but she refused. She said she didn’t want it to be leaked and reach her family or in-laws,” Dr Nusrat explained, adding that she knows of at least three other cases where female doctors have been secretly filmed.

Dr Nusrat happened to know someone senior in the police who spoke to the blackmailer, warning him he could be arrested for what he had done. The police officer made sure the video was deleted.

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t take further action, but we got the hole covered so that no-one could do it again,” says Dr Nusrat.

Other women shared experiences of being sexually harassed, including Dr Aamna (not her real name), who was a resident medical officer in a government hospital five years ago when she was targeted by her senior doctor, a powerful man.

“When he saw me with a file in my hand, he would try to lean over it, make inappropriate comments, and try to touch me,” she says.

She filed a complaint with the hospital administration, but says she was met with indifference. “I was told I had only been there for a short time, and asked what proof I had of this harassment. They said, ‘We’ve been unable to fix this person in seven years – nothing will change, and no-one will believe you’.”

Dr Aamna says she knows of other women who have managed to record videos of harassment, “but nothing happens – the harasser is merely transferred to another ward for a few months, then comes back”.

She had to complete her placement to qualify as a doctor, but moved as soon as it was over.

Testimony gathered by the BBC suggests her story is disturbingly common.

The root of the problem lies in a lack of trust and accountability, according to Dr Summaya Tariq Syed, the chief police surgeon in Karachi and head of Pakistan’s first rape crisis centre.

She describes her 25 years of service as a constant battle against violence and betrayal, and says she has been disappointed with how things are handled.

She recounts how, a few years ago when she was in a different role, she was shut in a room by colleagues who wanted her to change what she had written in a post-mortem examination report about someone who had been killed.

“They said, ‘Sign it or you have no idea what we’ll do to you’,” but she refused. Given the senior position of one of the people involved, she says, no action was taken against them.

Another female doctor at a government hospital in Punjab explains that it can be hard for women to report abuse.

“The [hospital] committees that do exist often include the same doctors who harass us, or their friends. So why would anyone file a complaint and make their life even more difficult?”

There are no official statistics available on assaults against female health workers in Pakistan. However, a report in the US National Institutes of Health in 2022 paints a troubling picture. It indicates that up to 95% of nurses in Pakistan have faced workplace violence at least once in their career. This includes assault and threats as well as verbal and mental abuse, from colleagues, patients and hospital visitors.

This tallies with a report in the Pakistan Journal of Medicine and Dentistry, which quotes a 2016 study of public sector hospitals in Lahore that suggested 27% of nurses had experienced sexual violence. It also cites a study from Pakistan’s north-western Khyber Pakhtunkha province that indicated that 69% of nurses and 52% of female doctors there had experienced some sort of sexual harassment in the workplace from other staff.

Dr Syed recounts a particularly disturbing attack that happened in Karachi in 2010: “A doctor at a government hospital lured a nurse to his hostel, where he wasn’t alone – two other doctors were there as well.” The nurse was raped and was so distraught that she jumped off the roof and was in a coma for about a week. “Nothing that happened was consensual. But she decided not to pursue the case.”

Dr Syed believes that society often blames victims and if the nurse had reported it “the blame would have fallen on her”.

Harassment and threats come from patients, their friends and families too, she says, describing how members of the public attacked her team while they were handling bodies in the mortuary last year.

“Two people had to ward off blows from a person who tried to hit me, just because I told him not to make videos.”

She registered a complaint with the police and is now waiting for the case to work its way through court. “We must continue our part of the fight – staying quiet will only strengthen the culprits.”

Other female doctors also describe a lack of security as a problem, especially in state-run hospitals, where they say anyone can walk in unchecked. At least three said people who attacked them were ordinary citizens who had entered the hospital while drunk. Drinking alcohol is largely banned in Pakistan.

Dr Saadia (not her real name) explains that several of her colleagues at a major government hospital in Karachi have been repeatedly sexually harassed. “It’s often people under the influence of drugs wandering into the hospital,” she says.

“One evening, a colleague was on her way to another ward when a drunken man started harassing her. Another time, a different doctor was attacked. Some other doctors managed to get rid of the man, but there were no security guards around.”

Nurse Elizabeth Thomas (not her real name) says incidents where drunk patients try to touch them are common. “We feel terrified, unsure whether to treat the man or protect ourselves. We feel utterly helpless. And there are no security staff to help us.”

Dr Saadia says they don’t even know “if the person sweeping the floor or roaming around the ward claiming to be staff is actually staff”.

Looking back at her time at a government hospital in Punjab five years ago, Dr Aamna says: “In remote areas, forget about security; they don’t even have proper lighting in the hallways.”

According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2023, there are 1,284 government hospitals in the country. Doctors say security measures are extremely poor.

Healthcare workers say many either lack CCTV cameras or have too few, and those that do exist often don’t function properly. They say thousands of patients and their families visit these hospitals daily, and attacks on medical staff have become common.

Dr Saadia recounts how she once had to hide after a patient’s relative attacked her for waiting for test results to arrive before administering an injection.

“He was a tall man, and he started yelling at me. I was pressed against the door. He threatened me, saying, ‘Give the injection now, or I’ll kill you’.”

Many of Pakistan’s nursing staff come from minority non-Muslim communities, which can make them vulnerable in other ways, says Elizabeth Thomas.

“I know many nurses who are harassed, and if they don’t comply, they’re threatened with accusations of blasphemy. If a nurse is attractive, they’re often told to convert their religion.

“We’re always left wondering how to respond because if we don’t do what they want, they might falsely accuse us of blasphemy. This has happened to nurses.”

On top of the abuse, female doctors describe enduring long, demanding shifts with a lack of basic facilities.

“During my house job, we went through times when, during a 30-hour shift, we didn’t have a room to rest in. We would go outside and rest in a colleague’s car for 15 minutes or so,” says Dr Saadia.

“When I was in the emergency ward, there was no toilet. We couldn’t go to the loo during 14-hour shifts. Even when we were menstruating, we couldn’t use a toilet.”

She says toilets for hospital staff were in other blocks, so far away that they didn’t have time to go and use them.

EPA

EPAThe BBC asked local health ministers in the four provinces where these women have worked to comment, as well as the national health co-ordinator in Islamabad but did not receive any replies.

Since the rape and murder of the trainee doctor in India, discussions have intensified among female doctors in Pakistan about how to ensure their own safety.

Dr Saadia says it has affected her deeply and she has changed her routine: “I no longer go to dark or deserted places. I used to take the stairs, but now I feel safer using the lifts.”

And Elizabeth Thomas says it has shaken her too. “I have a seven-year-old daughter, and she often says she wants to become a doctor. But I keep wondering, is a doctor safe in this country?”