AFP

AFPThe Assad family ruled Syria for more than 50 years with an iron fist. Now that has come to an end.

Bashar al-Assad became president after the death in 2000 of his father Hafez, who had ruled for almost three decades.

In 2011, he brutally crushed a peaceful, pro-democracy uprising, sparking a devastating civil war in which more than half a million people have been killed and 12 million others have been forced to flee their homes.

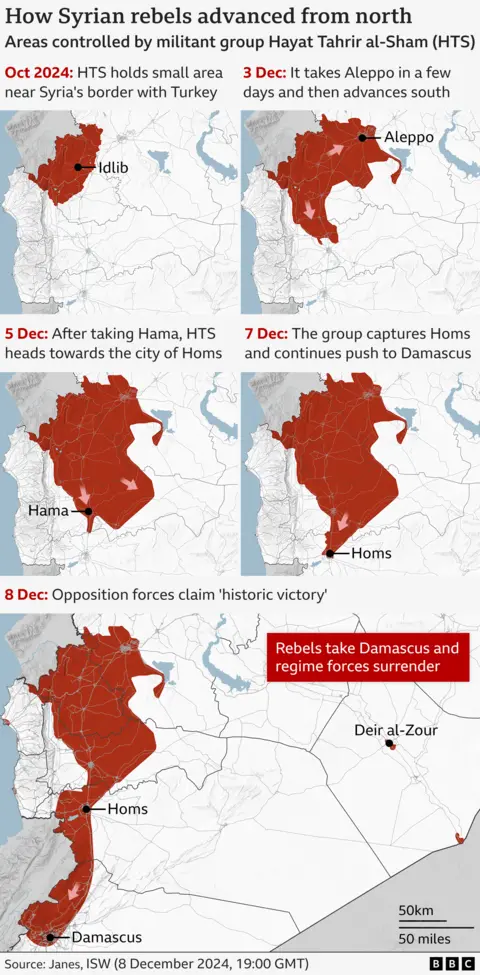

Thirteen days ago, the Islamist militant group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and allied rebel factions launched a major offensive in north-western Syria.

The rebels quickly captured the country’s second-largest city, Aleppo, then swept southwards down the highway to the capital, Damascus, as the military collapsed.

Russia announced that Assad had stepped down and left Syria on Sunday, hours after the rebels entered Damascus and crowds gathered on the streets to celebrate. It later emerged that Assad had flown to Moscow and been granted asylum.

HTS leader Abu Mohammed al-Jolani meanwhile arrived in Damascus and told Syrians: “The future is ours.”

How did the takeover unfold?

For the past four years, it had felt like the civil war was effectively over.

Assad’s government had regained control over most of Syria’s cities with the help of Russia, Iran and Iranian-backed militias like Hezbollah, and the front lines were largely frozen.

However, large parts of the country were still out of the government’s control.

The rebels’ last stronghold was in Aleppo and Idlib provinces, which border Turkey and where more than four million people were living, many of them displaced. It was dominated by HTS, but a number of allied rebel groups and jihadist groups were also based there. Turkish-backed rebel factions also controlled territory with the support of Turkish troops.

On 27 November, HTS and its allies launched their surprise offensive.

After three days, they took control of most of Aleppo – Syria’s second-largest city. They said they faced little resistance on the ground after the government rapidly withdrew its troops and security forces.

The Turkish-backed rebel factions meanwhile capitalised on the government’s retreat by launching a separate offensive on territory north of Aleppo controlled by a Kurdish-led militia alliance supported by the United States, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Assad vowed to “crush” the rebels with the help of his allies. Russian warplanes intensified strikes on rebel-held areas and Iran-backed militias sent reinforcements to help the military near Hama – the next city south on the way to Damascus.

But Hama fell to the rebels on Thursday, after several days of fierce battles that eventually prompted the military to withdraw.

The rebels declared their next goal was to take Homs, Syria’s third-largest city, and achieved that on Saturday night after only a day of fighting. At the same time, other rebel factions reached the suburbs of Damascus.

Early on Sunday, HTS-led rebels announced they had entered Damascus and released detainees at the country’s most notorious military prison, Saydnaya.

Less than two hours later, they declared: “The tyrant Bashar al-Assad has fled.”

The rebels also promised to build a “homeland for all, including all sects and social classes”.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group, reported that at least 910 people had been killed, including 138 civilians, since the start of the rebel offensive.

What is Hayat Tahrir al-Sham?

The Islamist militant group that led the offensive against Assad was set up in 2012 under a different name, al-Nusra Front.

Al-Nusra Front, which pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda the following year, was regarded as one of the most effective and deadly groups fighting President Assad.

But it was feared for its jihadist ideology, and was seen as being at odds with the largely secular main rebel coalition – the Free Syrian Army.

In 2016, Al-Nusra broke ties with al-Qaeda and took the name Hayat Tahrir al-Sham when it merged with other factions a year later.

However, the UN, US, UK and a number of other countries continue to consider HTS as an al-Qaeda affiliate and frequently refer to it as al-Nusra Front. The US named Abu Mohammed al-Jolani as a specially designated global terrorist and offered a $10m reward for information that led to his capture.

HTS consolidated its power in Idlib and Aleppo provinces by crushing its rivals, including al-Qaeda and Islamic State (IS) group cells. It set up the so-called Syrian Salvation Government to administer the territory according to Islamic law.

Reuters

ReutersWhy did the rebels succeed?

For several years, Idlib remained a battleground as Syrian government forces tried to regain control.

But in 2020, Turkey and Russia brokered a ceasefire to halt a push by the government to retake Idlib. The ceasefire largely held despite sporadic fighting.

HTS and its allies said on 27 November that they had launched an offensive to “deter aggression”, accusing the government and allied Iran-backed militias of escalating attacks on civilians.

But it came at a time when the government had been weakened by years of war, sanctions and corruption – with allies Russia and Iran preoccupied by other conflicts.

The Iran-backed group Hezbollah had recently suffered from Israel’s offensive in Lebanon. Israeli strikes had eliminated Iranian military commanders in Syria, and Russia was distracted by the war in Ukraine.

Without them, Assad’s forces were left exposed.

What happens next?

Outgoing prime minister Mohammed al-Jalili said on Monday that most members of his former cabinet were working with the rebels “so that the transitional period is quick and smooth”.

The rebels said in a brief statement that their forces were close to establishing complete control of Damascus and preserving public property. They also said Syria’s new government would begin its work as soon as it was formed.

The National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, which represents now-former opposition groups, said on Sunday that it was committed to “completing the transfer of power to a transitional governing body with full executive powers, paving the way for a free, democratic and pluralistic Syria”.

The statement made no mention of HTS, but its vice-president, Dima Moussa, told the BBC that the “transition requires coming together of all Syrian people, including those who are carrying arms”.

Meanwhile, the war continued in other parts of Syria.

HTS and its allies said their forces were advancing in the western countryside of Deir al-Zour, the largest city in eastern Syria.

Turkish-backed rebel factions fighting under the banner of the Syrian National Army were also advancing north-west of Aleppo into territory held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces.

Israel confirmed it was attacking suspected government chemical weapon and missile sites in Syria, saying this was to stop them falling into the hands of extremists. It also said it would keep a “limited” troop presence in what had been a demilitarised buffer zone in part of the Golan Heights because Syrian troops had abandoned their posts there.

Former Assad loyalists also appeared to be still in control of the Mediterranean coast and mountains in the west of the country. The region is a stronghold of Assad’s minority Alawite sect and also the location of two key Russian military bases – Hmeimim airbase and the naval base in Tartous.

How have world and regional powers reacted?

Russian media said Bashar al-Assad and his family had been granted asylum. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Russia had been as “surprised” as everyone else by what had happened and that Syria was “going through a very difficult period now, due to instability”.

Iran expressed a hope for “the swift end of military conflicts, the prevention of terrorist actions, and the commencement of national dialogue” with all parts of Syrian society.

Turkey said Syria was now at a stage “where the Syrian people will shape the future of their own country”. Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan said the new government “must be established in an orderly manner” and warned that “the principle of inclusiveness must never be compromised”.

US President Joe Biden said the collapse of the Assad government was a “fundamental act of justice” after decades of repression, but cautioned that the takeover by Islamist rebels created a moment of “risk and uncertainty”.

Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said the collapse of the Assad government was the “direct result” of his country’s action against Hezbollah and Iran.

Iraq, where powerful Iran-backed militias sent fighters to support the Syrian military in the civil war, said it supported efforts to open a dialogue in Syria “leading to the adoption of a pluralistic constitution that preserves the human and civil rights of Syrians”.

Jordan’s King Abdullah, whose country backed rebel factions at the start of the war, said Jordan respected the will and choices of the Syrian people. He stressed the importance of avoiding “any conflict that could lead to chaos”.

The European Union’s foreign policy chief, Kaja Kallas, called Assad’s fall “a positive and long-awaited development”, and said the bloc’s priority was to ensure security in the region.