This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

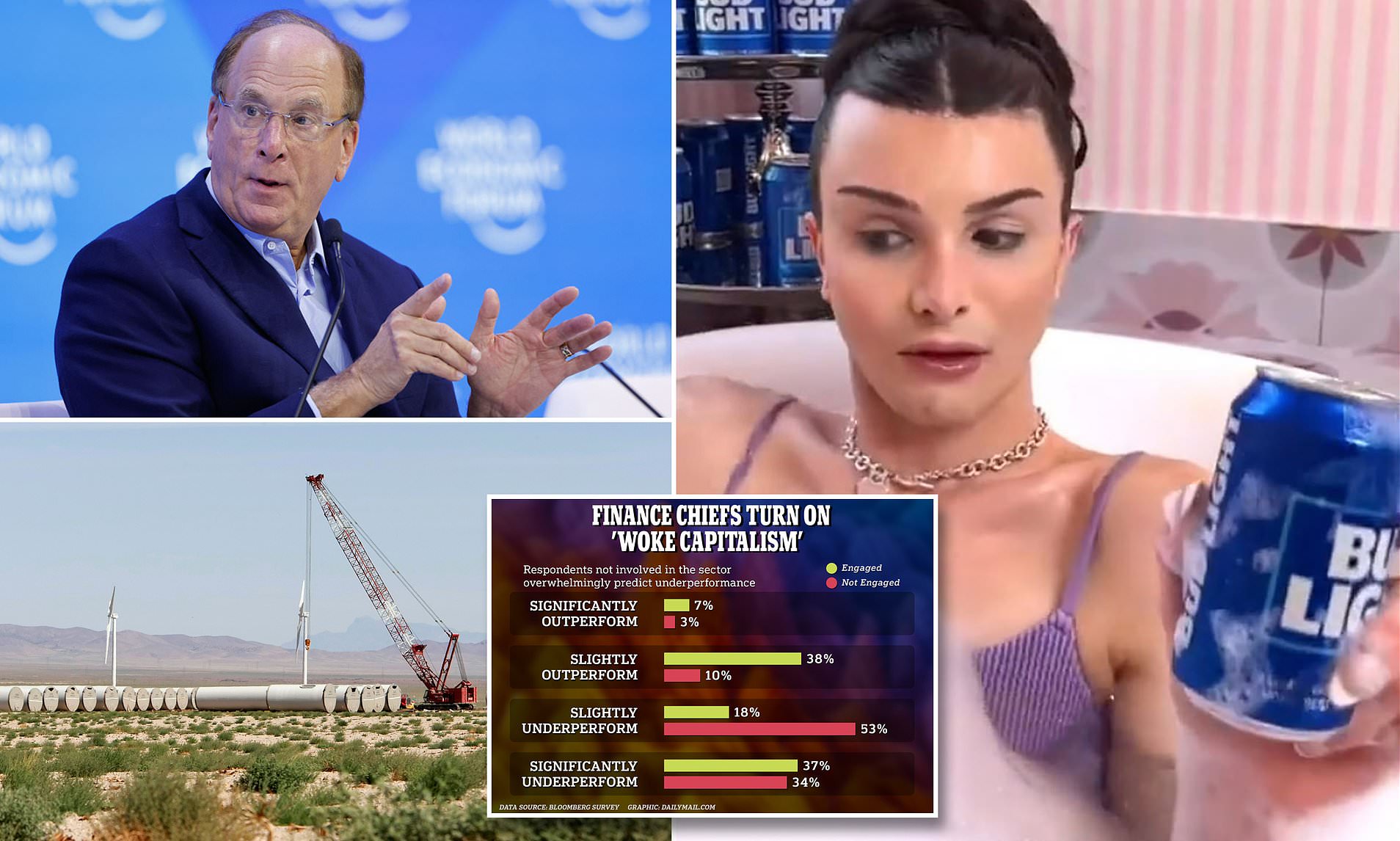

US Republicans this week took significant action against environmental, social and governance investing. Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed a sweeping anti-ESG bill that bans the state from issuing green or ESG bonds. The law also stops state pension funds from considering ESG criteria when voting at companies’ annual meetings.

Unlike in other states, where banking lobbyists have successfully watered down anti-ESG bills, the Florida law was enacted as originally proposed.

In Oklahoma, the state treasurer published a list of 13 financial firms deemed to be boycotting the energy industry, including JPMorgan, one of the largest fossil fuel financiers. BlackRock, Wells Fargo, Bank of America and State Street were also excluded from doing business with the state, Oklahoma said.

In an interview with our colleague Aime Williams, Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt said ESG companies are welcome in the state. But “for the shareholder return, we’re not going to allow [pensions] funds to be invested for someone’s political agenda,” he said. (Stay tuned for Aime’s full interview with the governor in the days ahead).

Today, Simon has an incredibly important piece about how companies are bringing people with criminal records into the workforce. And I look at the glaring absence of climate disclosures at Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. (Patrick Temple-West)

The next FT Moral Money Forum report will dig deep into carbon markets, and we want to hear from you. Do you favour carbon taxes? Can voluntary markets overcome quality concerns? Will compliance markets do more to push business to decarbonise? Share your thoughts here.

Warren Buffett’s nickname is the Oracle of Omaha, and there certainly is a religious fervour surrounding him at his company’s annual meetings each year. Shareholders come to pay homage to his investing abilities, but there is also reverence for his frugality and his promise to give most of his fortune to charity.

He seems like the type of ego-lite billionaire who would fit well with the environmentalist crowd. So why doesn’t Buffett seem to care about climate change?

Buffett’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, holds its annual shareholder meeting on Saturday. It is typically a big party. But this year, Buffett and his team are under mounting pressure to address climate concerns.

Norway’s oil fund, the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund, said this week it won’t support the re-election of any of Berkshire Hathaway’s board directors this year, in part because the company has failed to make climate risk disclosures.

Proxy adviser Institutional Shareholder Services has recommended investors vote against the company’s lead independent director Susan Decker over climate accountability. “The company is a significant greenhouse gas emitter and is not taking the minimum steps needed to understand, assess, and mitigate risks related to climate change,” ISS said.

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System and Caisse de Depot et Placement du Quebec have also filed a petition that is up for a vote tomorrow, demanding Berkshire publish a climate report.

Last year, BlackRock and Vanguard both voted for shareholder proposals at Berkshire Hathaway on climate disclosures as well as emissions reductions targets. Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t have adequate climate risk disclosures against all four pillars of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), BlackRock said.

Buffett controls more than 30 per cent of the votes at Berkshire Hathaway, making it almost impossible for outside shareholders to change things. Berkshire did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Buffett’s legacy as an investing sage is indisputable, as is his humility and good humour. But for some reason, he is being intransigent on climate. TCFD disclosures have become a bare minimum in the US. Why has Buffett shrugged off climate concerns — if only to serve as an example to the rest of corporate America?

At some point, Buffett’s climate stance might start to taint his reputation. Saturday’s shareholder meeting is likely to serve up some evidence. (Patrick Temple-West)

Paul Cowley’s memoir Thief Prisoner Soldier Priest recounts a life that took him from crime and homelessness to prison, and then from the British army to a priesthood in the Church of England. Now he has embarked on a new chapter — hiring people with criminal convictions to work for one of the UK’s largest supermarket chains.

Cowley’s unusual title — director of rehabilitation — reflects an approach that sets Iceland Foods apart from its peers in UK business.

Most big companies have made progress on providing opportunities for people who have been historically disadvantaged by their gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation. Few, however, have taken a similar approach to people with criminal records — who are often required to declare this at the outset of a hiring process, and then swiftly ruled out of consideration.

Many employers may not realise what a large demographic group this is: 27 per cent of working-age UK adults have a criminal conviction, mostly for relatively minor offences that led to a short prison sentence or none at all. In the US, about a third have a record of criminal conviction or arrest. At a time of acute labour shortages — Iceland Foods is currently advertising nearly 650 vacancies on its website — companies could profit by making smarter use of this section of the workforce.

Since taking on his corporate role in September, Cowley has interviewed 130 prison inmates nearing the end of their sentences, and given jobs to about 70. Of those, about half remain Iceland employees. The other half have dropped out — some failing drug tests, others not turning up for work — a setback that was to be expected, said Cowley, who worked extensively with ex-offenders during his time in the Church. “You know, prison affects people,” he told me.

Since joining Iceland’s board at the invitation of its founder Sir Malcolm Walker, Cowley has been working to overhaul its recruitment process. Applicants for jobs on the company’s website are now informed that it is actively seeking to hire more people with criminal convictions — a stark contrast with other companies’ practice of quiet exclusion.

Iceland may be an outlier in the UK, but companies have been much more active on this front across the Atlantic. JPMorgan Chase chief executive Jamie Dimon boasted last year that 10 per cent of the bank’s hires in 2021 had criminal records, and that (in contrast with Cowley’s experience so far) “retention rates for this population are very high”.

Companies including Walmart, Target and Home Depot don’t ask for details of criminal records until the later stages of the hiring process, giving applicants a better chance to impress their potential employers. Major corporations such as Microsoft and Verizon have lent their support to campaigns in various US states for legislative reforms to erase old convictions from individuals’ records.

In the UK, the FairChecks campaign is calling for reforms that would give adults a clean slate for childhood offences, and — after a certain period — for offences that resulted in a short prison sentence. Its backers include Lord Michael Hastings, a longtime advocate for smarter approaches to crime reduction. “We mouth these phrases of diversity, equity, inclusion — but when it comes to this section of people, all that goes out of the window,” he told me. “This is a resource of people that the economy needs.”

But businesses should seize the initiative rather than putting the focus on legislative change, said Ashish Prashar, who served a sentence for theft before a career that has included working for former prime minister Tony Blair and later as an advertising executive. “You don’t need to wait for government to pass laws,” he told me, “to give people a second chance, to fill vacancies, to move the economy forward.” (Simon Mundy)

Prominent climate diplomat Pete Betts has just months to live — but he still holds out hope for global action on the climate crisis. Don’t miss his moving exchange with the FT’s Pilita Clark.

Join us in London, or online, for the third annual Moral Money Summit Europe on May 23-24. Leading investors, corporates and policymakers will come together to discuss what needs to happen next to unlock a more sustainable, equitable and inclusive economy.

FT Asset Management — The inside story on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar industry. Sign up here

Energy Source — Essential energy news, analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here

Warren Buffett’s baffling blind spot