BBC News

BBC

BBCHead to the grocery store in the US and the shelves are stocked with jars of St Dalfour strawberry spread and Bonne Maman raspberry preserves – some of the more than $200m (£154m) in jams that Europe sends to America each year.

But try looking for American-made jelly in Europe, and you’re likely to come up short.

The US exports less than $300,000 in jam each year to the bloc.

It’s an imbalance that US company JM Smucker, one of the biggest sellers of such products in America, blames on a 24%-plus import tax its fruit spreads face in the EU.

“The miniscule value of US exports to the European Union is entirely attributable to the high EU tariff,” the company wrote in a letter to the White House this month, asking the Trump administration to address the issue as it prepares to levy “reciprocal” tariffs on America’s biggest trading partners.

“Reciprocal US tariffs on EU jams and jellies would serve to level the playing field,” the company said, noting that the highest US jam tariff is currently just 4.5%.

Globally, Trump’s push to deploy tariffs against close trading partners – many of which have average tariff levels similar to America’s – has generated anger and bafflement, while drawing warnings from economists about higher prices and other potential economic pain.

Some businesses in the US have echoed those concerns, but Trump’s calls for tariffs are also channelling longstanding frustrations many firms feel about foreign competition and policies they face abroad.

Smucker’s letter was one of hundreds submitted to the White House, seeking to influence the next set of tariffs, expected to be unveiled on 2 April.

Apple farmers raised the big disparity in import duties their fruit faces in countries such as India (50%), Thailand (40%) and Brazil (10%), as well as sanitary rules in countries such as Australia they said unfairly block their exports.

Streaming businesses flagged digital taxes in Canada and Turkey that they said “unfairly target and discriminate” against US companies.

The oil and natural gas lobby criticised regulations in Mexico that require partnership with the state-owned oil company and other policies.

The White House itself spotlighted uneven ethanol tariffs in Brazil (18%, compared with 2.5% in the US), car tariffs in Europe (10%, compared with 2.5% in the US) and motorcycles in India (until a few years ago, 100% vs 2.4% in the US).

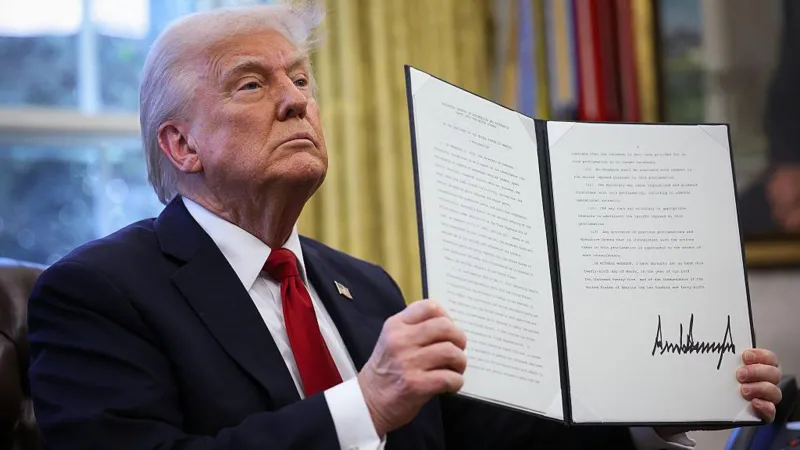

Trump has suggested that his plan for reciprocal tariffs will help remedy such grievances, pumping up his announcement as “Liberation Day”.

But even the businesses seeking action on their own issues have expressed hesitation about the president’s tariff-first, ask-questions-later strategy, which risks retaliation and a wider trade war.

With 2 April looming, there remains widespread uncertainty about the goals and scope of White House plans, especially as Trump launches a broadside of other duties.

“We’re going to be nice,” he said this week, at the same time as he announced potentially devastating tariffs on foreign cars and car parts. “I think people will be pleasantly surprised.”

India has already said it would lower its tariffs on motorcycles – an apparent bet that Trump’s tariffs are a strategy designed to gain leverage for trade talks.

But analysts warned that those hoping that Trump plans to use his reciprocal tariffs to negotiate changes elsewhere may be disappointed, as the president has also indicated he could be satisfied by simply hitting back.

“Some days it’s about revenge and just equalising things and other days it’s about lowering tariffs and then other days, third days, it’s about bringing manufacturing to the United States,” said William Reinsch, senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington thinktank.

“He’s used them all at different times – there’s not a single thread here that you can rely on.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe mismatch between the blunt tool of tariffs and the more niche issues firms want the White House to champion has led to a delicate dance, as businesses suggest tariffs in their own interest, while also hoping to avoid the repercussions of the kind of sweeping duties that Trump has suggested might be on the table.

For example, steel manufacturer NorthStar BlueScope Steel, which employs 700 people in the US melting steel from recycled metal, urged Trump to expand tariffs on steel and aluminium to parts.

At the same time, however, it asked for an exemption for the raw materials it needs, such as scrap metal.

Likewise, the lobby group for JM Smucker and other big food manufacturers, the Consumer Brands Association, warned against “overly broad and sweeping tariffs” that might end up making it more expensive for its members to import ingredients like cocoa, which are not made in the US.

“I don’t necessarily want the current administration to say, well, we’ll impose a tariff,” Tom Madrecki, the group’s vice president of supply chain resiliency, said at a recent forum about tariffs, hosted by Farmers for Free Trade.

“It’s this careful balance between yes, I want you to take an America First trade policy and action to counter unfair trade policies abroad … but maybe not quite in that way.”

Wilbur Ross, who served as Trump’s commerce secretary in his first term, said he thought business worries would dissipate as Trump’s plans become clear, calling 2 April a “big step”.

But he noted that the president saw little downside to using tariffs, viewing them as either a source of new revenue, or a way to reduce imports and encourage more manufacturing.

“He’s very committed,” he said. “People should have known that something like this was coming because he’s been talking about it for many, many years.”

Republicans, traditionally the pro-trade party, have stayed supportive of Trump’s strategy, even as tariff announcements have been blamed for the recent stock market sell-off and weakness in recent surveys of business and consumer confidence.

At a recent hearing on trade, Representative Jodey Arrington, a Republican who represents Texas, acknowledged that there might be “some pain associated on the front end” but maintained Trump’s focus on the issue would create opportunities for his constituents in the end.

“It just seems to me that it’s un-American to not fight for our American manufacturers, producers and workers to simply have an even playing field,” he said.

“We’re simply attempting … to reset those relationships such that we’re playing by the same set of rules,” he added. “Then everyone wins.”