OK, central banks still seem far away from actually cutting interest rates — the much-vaunted Pivot! that many investors have been praying for — but the overall pace of tightening has collapsed.

This may seem like an odd thing to say, after the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank all jacked up their main policy rate this spring, with the BoE announcing another quarter point rise to 4.5 per cent just yesterday.

However, in the three months to April there were only 48 rate increases across the 57 central banks that the FT tracks — about half those over the same period for most of the second half of 2022 and the lowest figure since the three months to February 2022.

This is because many central banks in emerging markets have already paused their monetary tightening, with Canada also joining their rank as it held rates unchanged in the last two meetings. Here’s William Jackson, chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics:

Most EM central banks have drawn their monetary tightening cycles to a close now and, if history is any guide, it looks like the conditions will be in place for an easing cycle to start from around July/August.

In Latin America, Brazil has left its policy rate unchanged since August last year, Chile hasn’t increased rates since October and Peru has been on pause since the start of 2023. Across 12 countries in central and Latin America there were 11 rate increases in the three months to April, less than half the number in the summer last year.

In eastern Europe, where inflation has been higher than in the rest of the continent, the picture is similar. In the three months to April, there were 12 rate increases across 18 countries, down from a peak of 24 rate rises in the three months to February 2022. This comes as Romania paused its rate increases at the start of the year, Poland in September 2022, while Romania and the Czech Republic announced their last increase in June 2022.

The EM pause is largely because many developing countries started ratcheting up interest rates far earlier and with more alacrity than western central banks to quell inflation. Brazil, for example, lifted its Selic target rate already in March 2021, nearly one and half year earlier than the ECB, and it now stands at a hefty 13.75 per cent — more than twice as high as the current inflation rate.

So when is the pivot to lower rates going to start?

Some countries — such as Vietnam, Uruguay, Costa Rica and Angola — have already cut interest rates. Capital Economics predicts that South Korea, Hungary and Chile will be among the next to ease monetary policy, and markets are pricing some probability of a rate cut at the next meeting for India, Poland, Colombia, Chile, Brazil and the Czech Republic.

Here’s Jackson again, with his emphasis below:

Unsurprisingly, having been the first to hike, EM central banks also brought their tightening cycles to an end long before DM central banks . . . So the monetary policy tide seems to be shifting.

. . . Historically, EM central banks have tended to turn from tightening to loosening monetary conditions quite rapidly. In the past few decades, central banks have waited around four months on average between ending their hiking cycle and delivering their first rate cut. Typically, the larger the preceding tightening cycle, the quicker the move to interest rate cuts.

But as every macroeconomist knows, Réal Pivöts can only be produced in the Washington region of America, with some also arguing that the terroirs in Frankfurt, London and Tokyo are not to be sniffed at. When are we likely to see those hit the market?

Well, markets seem pretty convinced that the Fed pause is now in, and the economic fallout from tightening credit conditions will spur cuts later this year. Others major central banks expected to follow.

George Cole, economist at Goldman Sachs said that his base case “is that G10 central banks will in general complete their hiking cycles relatively soon, before ultimately lowering rates in years to come.”

Not that investors should be looking forward to that, notes Saira Malik, chief investment officer at Nuveen.

Consensus expectations call for interest rate cuts by the end of 2023, but we expect rates to remain higher for longer. A Fed pivot may sound like a tailwind for risk assets, but such a shift won’t occur in a vacuum. In fact, what ultimately causes the Fed to cut — a slowing economy that devolves into a recession — is bound to be a negative for markets. Until then, continued tightness in the labor market, along with stubbornly sticky areas of inflation and a contentious political landscape in Washington, D.C., should cause volatility to pick up in the coming weeks.

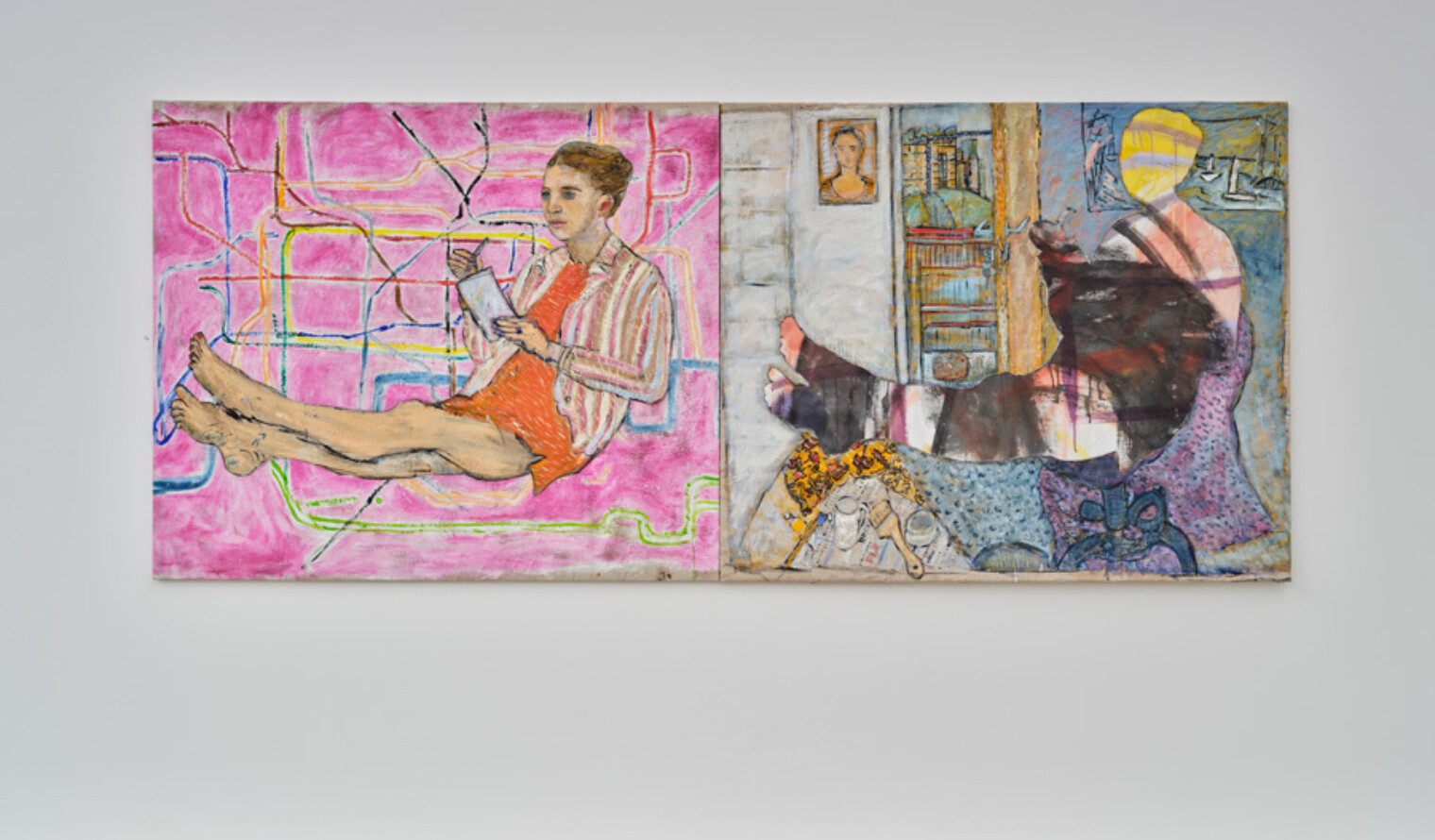

The Pause — visualised