This article deals with sudden death, bereavement and grief. BBC Action Line can direct you to help with these issues.

For those watching on the beach on the morning of Wednesday, 28 April 1993, the first bodies were revealed by the rising sun.

Fishermen searched in and out of creeks, divers went out in boats and a helicopter hovered overhead.

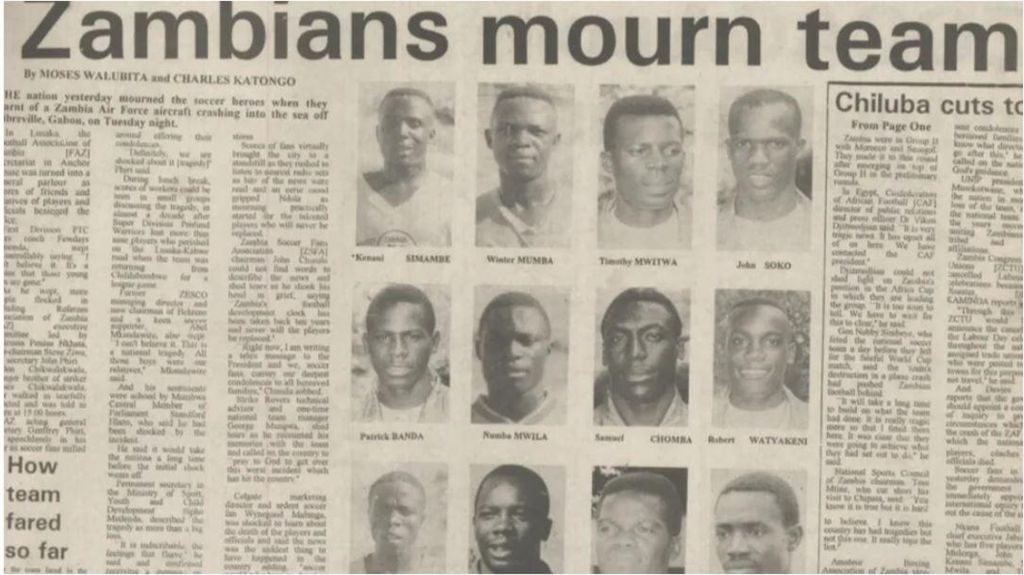

By lunchtime, black kit bags, wreckage and the remains of 24 of the 30 people aboard the plane had been reclaimed from the Atlantic Ocean and brought ashore in Gabon. No more bodies would be found.

So begins a story that touched generations across two decades, laid bare a nation’s soul, and delivered triumph, just as unexpectedly as disaster.

Four thousand miles away, another kit bag had been packed and its owner, one of Africa’s best footballers, was preparing to go for a long run.

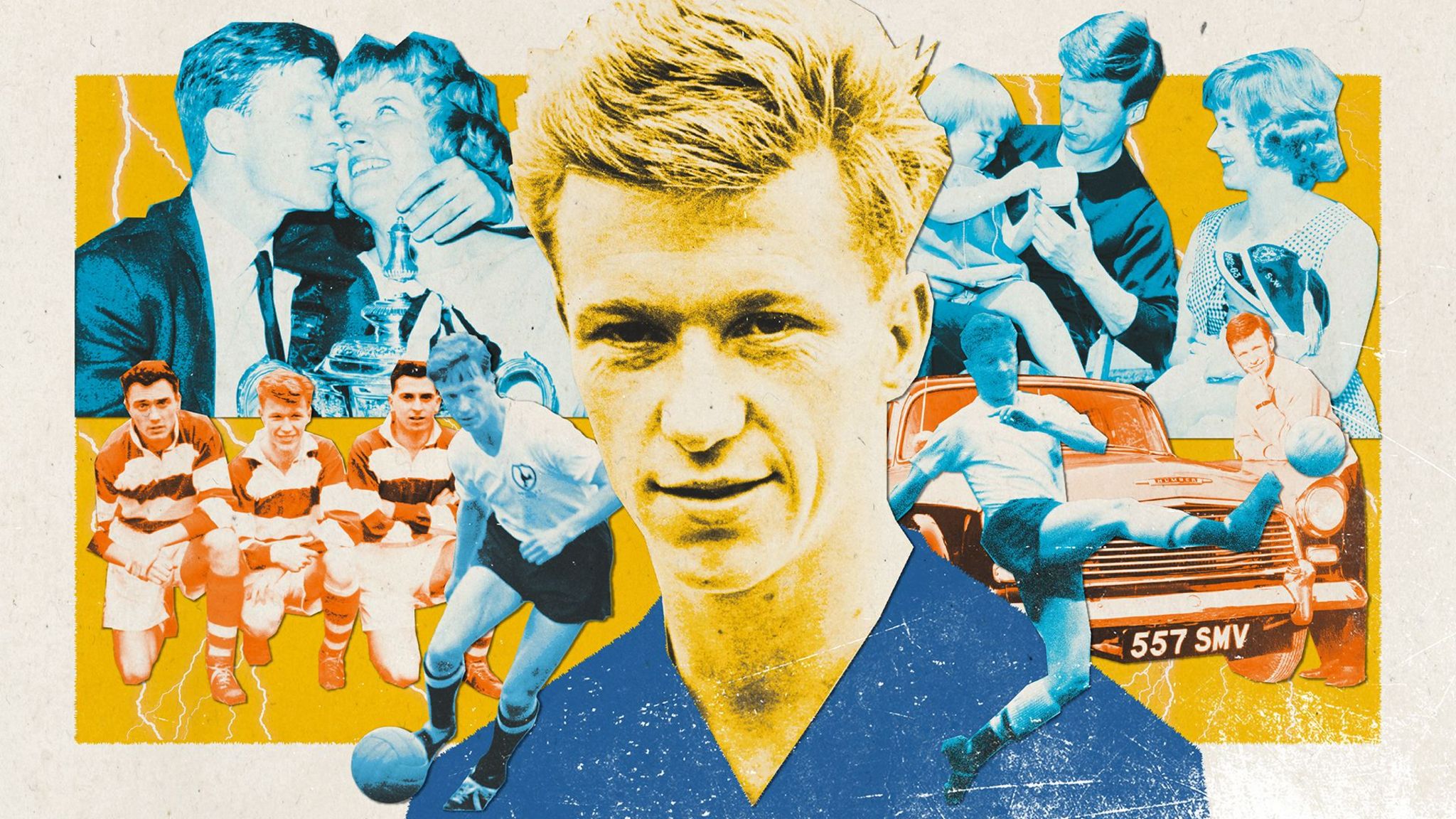

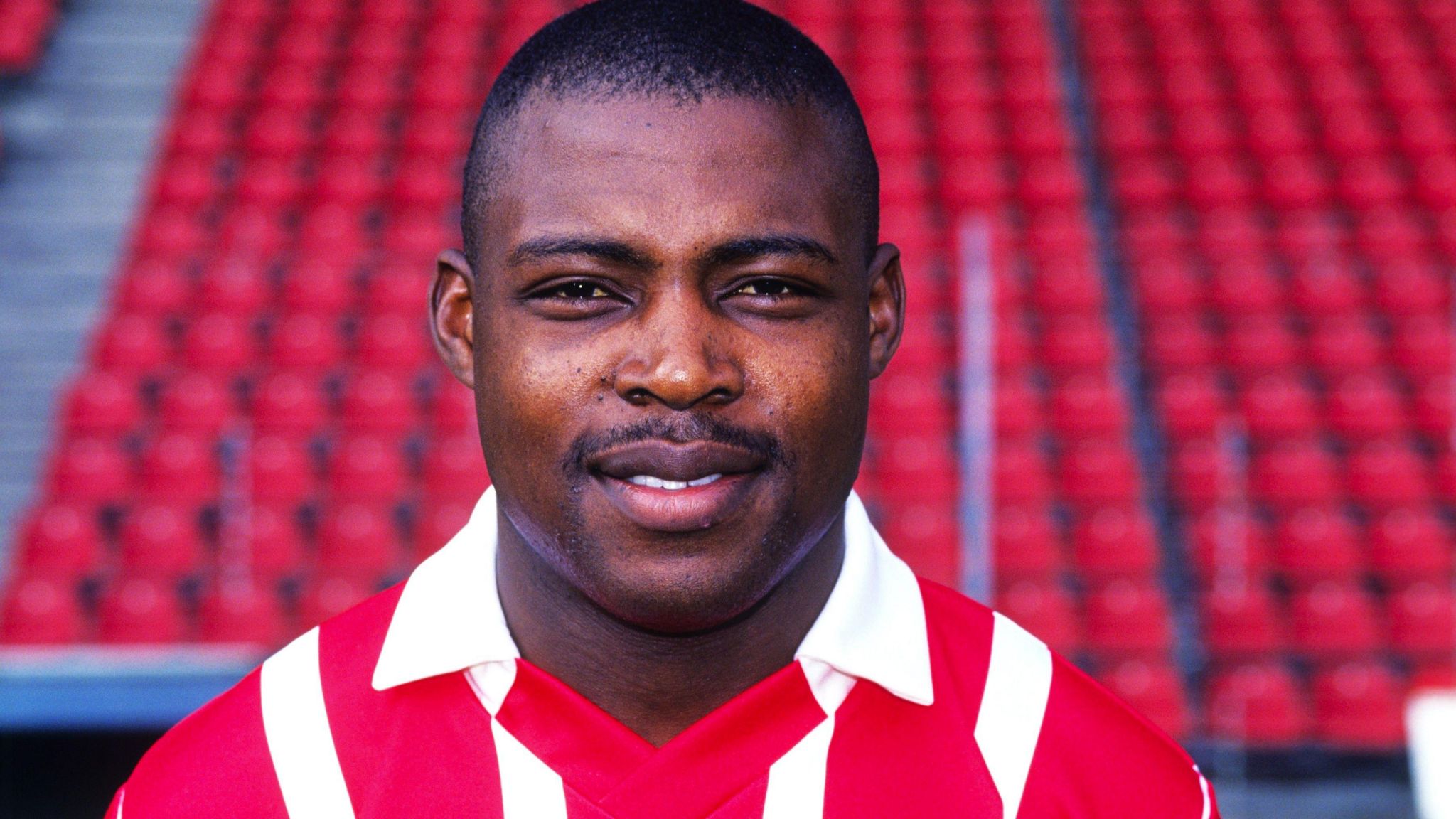

Kalusha Bwalya was Africa’s Player of the Year in 1988.

Earlier that year, he had scored a hat-trick as Zambia thrashed Italy 4-0 on the way to the Olympic quarter-finals in Seoul.

Since then, he had moved to PSV Eindhoven, partnering Brazilian great Romario up front for the reigning Dutch champions.

Bwalya and two other Europe-based players were due to meet up with their Zambia team-mates in Senegal, before the first of four qualifiers for the 1994 World Cup.

Zambia’s stellar generation of players were strongly fancied to take their nation to the tournament for the first time.

With the prospect of a flight itinerary taking him from Amsterdam to Dakar via Paris, Bwalya wanted to stretch his legs and clear his mind.

But, before he could leave on his run, his landline rang.

In the early 1990s, mobile phones were a rare luxury. One Bwalya didn’t have. Calls could not be ignored.

Bwalya picked up the receiver.

“It was the treasurer of the Football Association of Zambia,” says Bwalya.

“The first thing he said to me was, ‘Kalu, you have to delay your flight. There has been an accident.’”

For Zambia’s population, its football team was a beacon of hope.

The price of copper, the country’s primary export, had almost halved in the past four years, tanking the economy. Income had dropped sharply.

President Frederick Chiluba had declared a national state of emergency, alleging that a coup plot against him had been uncovered.

The football team though were a source of pride.

They were known as Chipolo-polo, the Copper Bullets.

It was a nickname derived from Zambia’s main industry and the team’s attacking, aggressive style.

The team had just returned from a 3-0 win over Mauritius in an Africa Cup of Nations qualifier.

They had an eight-year unbeaten home record and were a band of brothers at the peak of their powers.

As far as Zambians were concerned, USA ’94 was beckoning.

To get there they would have to top a qualification pool of three, trumping Morocco and Senegal in home-and-away ties.

First up, Senegal away.

As usual it was a DHC-5 Buffalo military plane that would take them there.

With the recession eating into its funding, the football association couldn’t afford commercial flights.

Instead the DHC-5 Buffalo, an 18-year-old twin-propeller aircraft, early models of which had been used in the Vietnam War, would lumber across the vastness of Africa.

It was not built for long-haul trips so it would have to make regular refuelling stops.

And it was showing its age. Six months earlier, while flying over the Indian Ocean en route to play Madagascar, the pilot had actually told the players to wear their life jackets.

When Zambia’s domestic-based players turned up to the airfield outside the capital city Lusaka to board, Patrick Kangwa, a member of the national team selection committee, met them.

He told 21-year-old midfielder Andrew Tembo and third-choice goalkeeper Martin Mumba that they wouldn’t need to travel. They were dropped from the squad.

Pride was hurt and hot words exchanged on the tarmac.

It was a standard selection decision, but, on this day, it decided who would live and who would die.

Those who did get onboard faced a daunting itinerary. The Buffalo planned to touch down and refuel in the Republic of Congo, Gabon and Ivory Coast before finally arriving in Dakar, Senegal’s capital.

In reality, it never made it beyond Gabon.

The Zambian government has never released the report into what happened to the flight.

But in 2003, the Gabonese authorities said that almost immediately after take-off from the capital Libreville, the plane’s left-hand engine stopped working.

The pilot, tired from flying the team back from Mauritius the day before, shut down the right-hand engine by mistake.

The heavy plane, suddenly without power or lift, plunged into the ocean a few hundred metres from the Gabon coast, killing all 30 people on board.

Back in the Netherlands, Bwalya, his run forgotten, saw the news he already knew break on television.

“There was a lady reading the news and the Zambian flag was behind her,” he remembers.

“She said, ‘the Zambian national soccer team traveling to Dakar, Senegal, for a World Cup qualifier has crashed. There are no survivors’.

“Ambition – as a young person, brothers, team-mates, the spirit of the group – was lost in one day. But it seems like yesterday, it’s so clear in my mind.”

Kangwa – the official who had sent the selected players on their way in Lusaka – flew to Gabon.

At a stroke, his role had changed from picking players to identifying their remains.

“The bodies had been in the water for some time so some had started to change in state,” he says in BBC World Service podcast Copper Bullets.

“I had to try and say, who’s this, who can this be?

“After that, I cried, we all cried. None of us thought that we would find ourselves in a place where we would see our colleagues in pieces.”

Meanwhile, Bwalya arrived in Lusaka, where reality sank in.

“We went to receive the bodies, and, one by one, they took the coffins off a plane to be transported to the Independence Stadium,” he says.

“That was when I realised I won’t see the team – the one I had travelled with in the same plane a few months earlier – again.”

On 2 May 1993, more than 100,000 Zambians came to Independence Stadium, where Zambia played their home matches, for a funeral.

Most of those attending stayed in the streets because the stadium’s capacity was only 35,000.

Following an all-night vigil and a service of remembrance the players were laid to rest in a semi-circle of graves.

Each grave has a tree planted in front of it in a memorial garden called Heroes’ Acre, 100 metres to the north of the stadium.

One commemorated the life of the legendary Godfrey Chitalu, a fabled goalscorer who became the team’s coach.

Another was dedicated to Bwalya’s room-mate, David ‘Effort’ Chabala, who had kept the clean sheet in the Olympic demolition of Italy.

Twenty-three year-old Kelvin Mutale was also among the dead. Two-footed, good in the air and two years into his international career, he had emerged as Bwalya’s strike partner and had just scored all three goals in the win over Mauritius.

“Derby Makinka was one of the best players that Zambia has ever produced in the number six position,” remembers Bwalya. “He was a tank.

“We had a world-class player in every position.

“I can still feel being in the changing room with the boys, I can still see the boys, how happy they were, and it’s a good past.”

Amid the shock and loss, a big question loomed: what would Zambia do now?

Bwalya thought he knew.

“I thought that Zambia was not going to play (again),” says Bwalya. “I was convinced that, there goes the ambition of us doing anything.”

But, a phone call from the country’s president, convinced him otherwise. The search for a new team – to be built around Bwalya – was on.

Twenty coaches gathered in Lusaka to give trials to 60 players. A squad of disparate hopefuls was then chosen and sent to Denmark for a six-week training camp at the expense of the Danish government.

They were greeted at Copenhagen airport by their new, temporary coach.

Roald Poulsen had pedigree. The 42-year-old had won both the Danish league title and cup with Odense, but his task of creating a competitive team for the World Cup qualifiers was formidable.

“I had no clue what I was going to do,” he admits. “I had no idea about the players and no idea about the background, no idea about the society itself, anything about Zambian football.

“I was a little bit worried when I saw the standard of the players. They didn’t know whether they were good enough.”

The players had to adjust too. Most had never left Africa before. Poulsen had to reassure them a post-training jog through Danish forest was safe, explaining that the risk of a lion attack was lower than in Zambia.

Bwalya found a group bonded by a common purpose and sense of duty.

“Everybody felt like they had to do something extra for the fallen heroes,” says Bwalya. “You knew that, I am a replacement but I am doing it on behalf of somebody, I’m stepping in for somebody.”

On 4 July, was their chance to step up.

Almost exactly two months after the funerals, Zambia’s 1994 World Cup qualifying campaign belatedly began against Morocco in Lusaka.

“I was with the captain’s armband and we were lining up,” remembers Bwalya.

“I looked behind to see that everybody is in place. The first person behind me was always Effort Chabala. Now, I saw all new faces.”

After just 10 minutes, Morocco led through a spectacular goal by Rachid Daoudi. In the stands, the home fans called upon the past to help the present.

“The people on the upper tier that faces the memorial site turned around and they started to appeal to their deceased players, their brothers,” remembers journalist Ponga Liwewe.

“They said, ‘can we, with your help, get back into the game?’”

Zambia could.

Just after the hour, Bwalya hit a magnificent equaliser from a free kick and within 10 minutes, Johnson Bwalya, no relation, won it with a second goal.

“It felt like we had come back from the dead,” Liwewe says.

“The whole nation was on its feet. We were resurrected. That’s an appropriate word to describe what we were feeling. We felt we can take on the world again.”

Ultimately though they would fall short of the World Cup itself.

Going into the final World Cup qualifier, away to Morocco in October 1993, all Zambia needed was a point to reach USA 1994.

They lost 1-0.

Six months later, they surprised everyone again, but suffered once more.

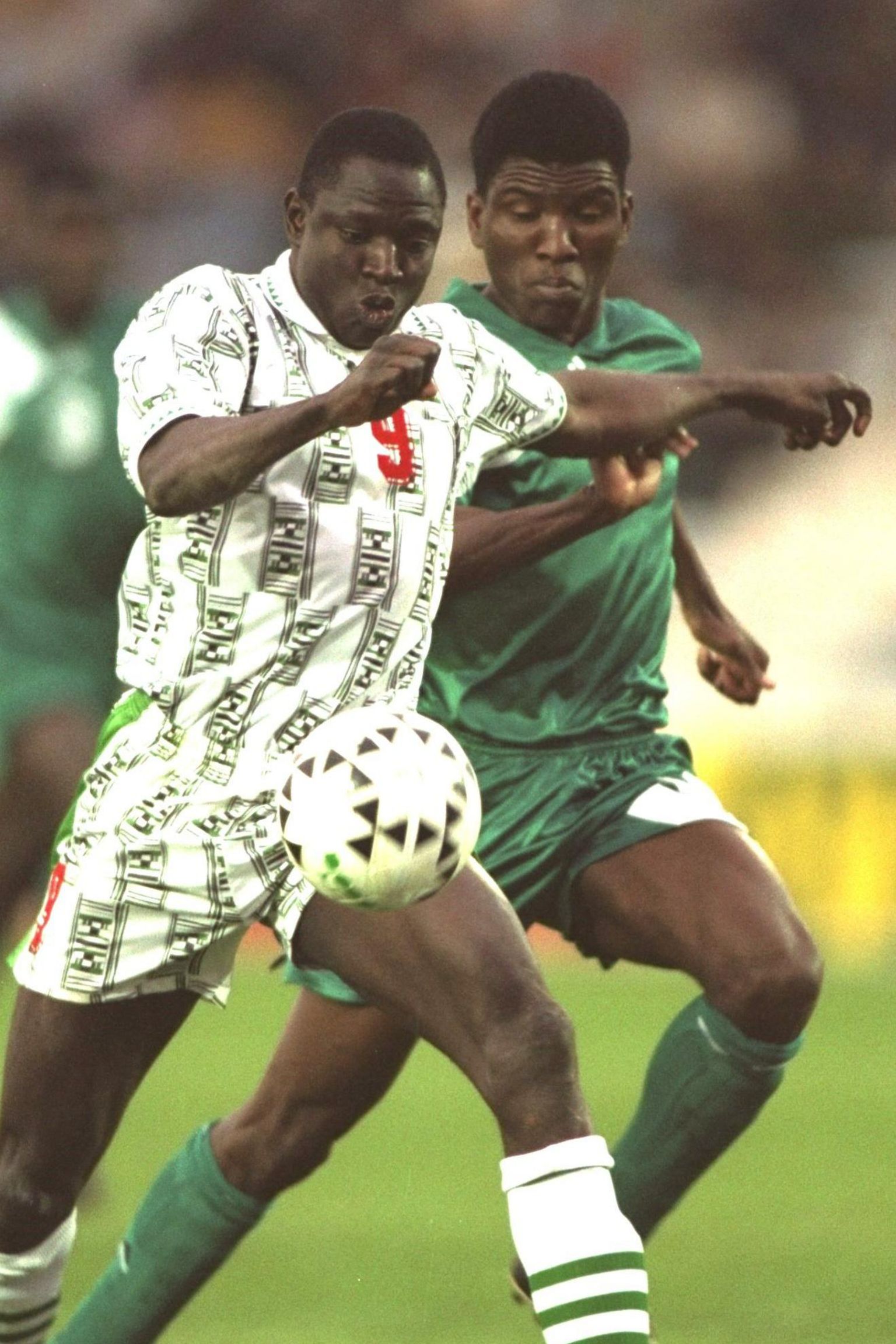

Against the odds, they made the 1994 Africa Cup of Nations final against Nigeria.

Elijah Litana gave Zambia the lead in the fourth minute, but two goals from the Super Eagles’ Emmanuel Amunike wrestled the title out of the Copper Bullets’ grasp.

In less than a year, Zambia had lost a team, fashioned another, and come agonisingly close to both World Cup qualification and Afcon triumph.

“It was a year that you had to age 10 years in order to fit in exactly what had happened,” reflects Bwalya.

“The fallen heroes, wherever they were, they were looking upon us and saying, ‘Yeah, good effort. You guys are doing well. Keep going.’”

Zambia would finish third in Afcon two years later and then retreat into obscurity for 16 years.

Zambia’s squad for the 2012 Africa Cup of Nations was short on star power.

Most of the players played in their domestic league, South Africa or the Democratic Republic of Congo. Captain Chris Katongo was based in China.

Unsurprisingly, they were 40-1 outsiders to win it.

Their coach was Frenchman Herve Renard, who had worked as a cleaner before breaking into football coaching. He was still to win a trophy after a decade in his new career.

Yet, they defied expectations.

Zambia topped a group containing a misfiring Senegal, saw off Sudan in the last eight, before a fine-counter-attacking performance upset Ghana in the semi-finals.

The final would bring them face to face with the past.

The tournament had co-hosts: Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. However, Zambia’s path through the draw had, so far, kept them exclusively in Equatorial Guinea.

“The only match we were going to play in Gabon, in Libreville, was the final,” says Bwalya, by then the President of Zambia’s football association.

The final was to be played less than 10 miles from where the 1993 team had perished off the Gabon coast.

“I said to the coach, I think it’s better that we make a connection so that the old team meets the new team,” says Bwalya.

“I made it known that, when we arrived, the first thing that we were going to do was visit the site.”

Three days before the final, Bwalya, Katongo and Renard were among those who cast flowers into the surf where, two decades earlier, bodies, boots and bags had washed up.

“When we moved out from the site of the plane crash, we were in the bus and I see players quiet a little bit,” says Katongo, who was 11 in 1993.

“Even if somebody was listening to their music, there was something (else) that he was thinking and trying to digest.

“From that moment, everybody said, ‘this is it guys. We just need to work as a team to achieve what these people wanted to achieve who perished here in Gabon.’”

Bwalya too could see that the players’ mindset had shifted.

“The boys believed that they are not only playing for themselves, that they’re also playing for the fallen heroes and that meant a lot more than just playing in the final.”

Renard’s pre-match team talk did not focus on Didier Drogba, Yaya Toure or any of Ivory Coast’s other stars. It didn’t focus on tactics.

Instead, it was all about what they had experienced together on the beach.

“Think about all the players and all the people who were in this plane and died for your country,” he told the players.

“Think about their families, think about your country. We have to do it. We can’t miss this fantastic chance.”

The game matched his speech for drama.

In the second half, with the game still scoreless, Drogba, at the peak of his Chelsea powers, smashed a penalty over the bar.

Extra-time couldn’t divide the teams either.

Both side converted their first seven penalties.

Both missed their eighth.

But finally, with a kick to win it, Zambia’s Stoppila Sunzu strode to the spot.

The defender sang a song of praise as he prepared to start his run-up, slipped just before connecting with the ball, but still buried his shot into the bottom corner.

His team-mates, who had been on their knees in prayer in the centre circle, burst forward to celebrate.

Nineteen years previously, a plane had flown from Gabon to Zambia returning the dead to their final resting place.

Now, another would made the same journey, carrying a golden trophy and a glory that transcended generations.