BBC

BBCA nature reserve in the Philippines, which has been lauded by top climate activists and film stars, has come under a concerted disinformation attack on social media as it fights to continue its work, a BBC investigation has found.

A network of nearly 100 fake Facebook accounts and pages were found to be spreading misleading claims about the Masungi Georeserve and its keepers. Most were taken down after the BBC asked Meta, Facebook’s parent company, about these accounts.

Despite gaining international recognition for its reforestation efforts in the fight against climate change, the reserve is under pressure from illegal loggers, land grabbers, and quarrying companies.

A spokesperson for the reserve said it was being “ganged up on” by local politicians, businesses and some officials in government. The environment department, which has proposed ending a reforesting contract with the reserve, denied the claim.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is not clear who controlled the network, but evidence seen by the BBC suggests that a public relations consultant who states on his social media profile that he has expertise in “reputation management” was linked to pages involved in the campaign.

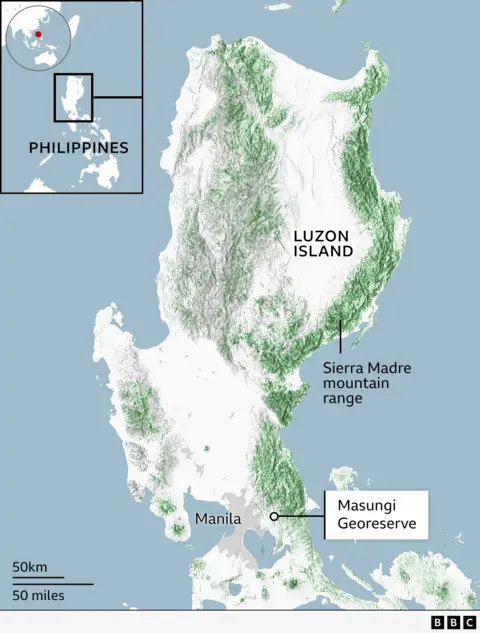

Located east of Manila, the Masungi reserve is a popular eco-tourism destination, known for its lush rainforest and gravity-defying limestone formations. Supporters include climate activist Greta Thunberg and Hollywood superstar Leonardo DiCaprio.

The reserve has been trying to fend off illegal business activities for years, but this particular smear campaign is understood to have started in recent months.

“We’ve seen misleading information, trying to manufacture dissent against work that we do as environment defenders,” says Billie Dumaliang from the Masungi Georeserve Foundation.

These online attacks have appeared against a backdrop of physical violence against people involved in protecting the environment in the Philippines.

Two forest rangers who work for the Masungi Georeserve were shot and wounded in 2021. And campaigning group Global Witness says the Philippines ranks as the most dangerous place in Asia for environmental defenders, with 298 people killed since 2012.

”Online propaganda can be quite important in creating a fear factor for the people who work in Masungi,” says Regine Cabato, a Filipino journalist with experience covering disinformation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy investigating this propaganda, BBC Verify identified a pattern of fake accounts and pages seemingly working together as part of the smear campaign.

Suspicious features included profile pictures showing K-pop stars, cats and models, rather than real people. Many of these accounts were created within hours of each other, and had very few friends.

But it was the content that they posted which made them stand out the most: in the last few months, they repeatedly posted content critical of the Masungi Georeserve Foundation.

“Suddenly the owners are making a lot of money,” posted one user, questioning the Masungi Georeserve’s entire operation.

“This protected area is owned by the people. Don’t be arrogant!” wrote another, along with an image telling the reserve to “stop masquerading as a protector of nature”.

“This is something we’ve seen play out during elections against certain political targets, and sometimes it’s something we’ve also seen deployed against private individuals,” says Ms Cabato.

“There is a lot of power and a lot of money that goes into turning the wheels of this machine.”

The campaign appears to have begun this year, around the time the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) proposed scrapping the 2017 contract that handed the Masungi Georeserve Foundation control over the vast majority of the land it holds – some 2,700 hectares – for reforestation purposes.

The move was criticised by a number of international celebrities, including Filipino actress and singer Nadine Lustre, Greta Thunberg and Leonardo DiCaprio – who, in an Instagram post, called on the Philippine president to “protect Masungi”.

Allow Instagram content?

When news outlets posted on Facebook about celebrity calls to “#SaveMasungi”, their posts drew the attention of the small army of fake accounts identified by the BBC.

Under those posts, they left comments defending the environment department’s proposal and attacking celebrities like DiCaprio over their intervention.

“Don’t be a loser Leonardo,” wrote one user.

“The DENR saw sketchy behaviour a long time ago,” posted another.

In addition, several of these accounts went on to share content from the DENR’s own social media accounts, or from pages supportive of the department’s work.

The DENR denies having any links to these accounts and pages.

But the department plays a dual role in the Philippines, which critics say is contradictory: it issues mining and quarrying permits, while also employing hundreds of forest rangers to protect the Sierra Madre, the country’s longest mountain range.

Podcast: An (online) storm in a Philippine rainforest

The BBC asked Meta about the accounts that seemed to be operating as an organised network, and the company confirmed that a cluster of accounts was engaging in inauthentic activity.

It took down most of the accounts and pages identified as part of the BBC investigation, saying they “engaged in deceptive, spammy activity, including amplifying content using fake accounts to make it appear more popular than it was”.

But it stopped short of linking this network to any third party.

“It seems like we’re being ganged up on by local politicians together with some people from the DENR, together with their cohorts in these destructive industries,” says Ms Dumaliang from the Masungi Geoserve Foundation.

The environment department denies this claim.

In a statement, the DENR told the BBC it had “no involvement in any social media campaign, activity, or other online tactics aimed at influencing public opinion in a negative manner”. It also described its communication efforts as transparent, accurate and fair.

While we do not know who ultimately controlled the network of accounts and pages, the BBC found evidence linking one individual to the campaign.

Facebook/OfficialBenPablo

Facebook/OfficialBenPabloOn social media, Ben Pablo described himself as a public relations consultant who specialised in “reputation management” and “social media marketing”.

But he placed ads on behalf of pages that were part of the campaign, according to Meta’s ad library, which lists all adverts placed on Facebook.

Mr Pablo did not respond to the BBC’s repeated requests for comment.

But since we first approached him, several of the pages that we believe he was linked to have been deleted, along with Mr Pablo’s own social media accounts.

In recent months, Mr Pablo has also bought Facebook adverts promoting Senator Imee Marcos, the sister of the current president, Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

Although there is no evidence linking her to this campaign, the BBC asked the senator’s team whether she had ever employed Mr Pablo, but did not get a response. Whether Mr Pablo was acting alone remains unclear.

But, despite the impact that online disinformation may have on the lives of those looking after Masungi, Billie Dumaliang seems undeterred.

“Every time we see the landscape, the sunset unobstructed, we are reminded of the reason why we’re doing this: it is to preserve this special place.”