UCL

UCLA remote cluster of Scottish islands could help solve one of our planet’s greatest mysteries, scientists say.

The Garvellach islands off the west coast of Scotland are the best record of Earth entering its biggest ever ice age around 720 million years ago, researchers have discovered.

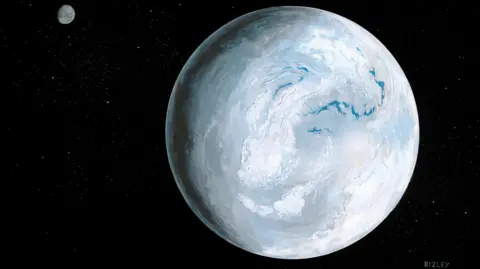

The big freeze, which covered nearly all the globe in two phases for 80 million years, is known as “Snowball Earth”, after which the first animal life emerged.

Clues hidden in rocks about the freeze have been wiped out everywhere – except in the Garvellachs. Researchers hope the islands will tell us why Earth went into such an extreme icy state for so long and why it was necessary for complex life to emerge.

SPL

SPLLayers of rock can be thought of as pages of a history book – with each layer containing details of the Earth’s condition in the distant past.

But the critical period leading up to Snowball Earth was thought to be missing because the rock layers were eroded by the big freeze.

Now a new study by researchers at University College, London, has revealed that the Garvellachs somehow escaped unscathed. It may be the only place on Earth to have a detailed record of how the Earth entered one of the most catastrophic periods in its history – as well as what happened when the first animal life emerged when the snowball thawed hundreds of millions of years ago.

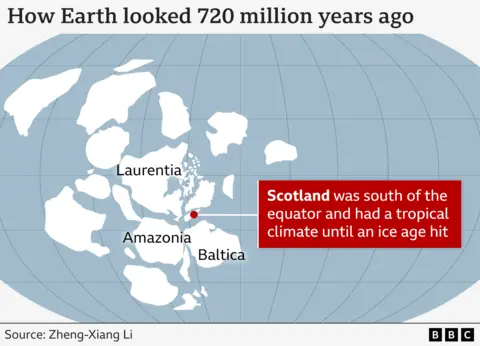

Back then Scotland was in a completely different place because the continents have moved over time. It was south of the Earth’s equator and had a tropical climate, until it and the rest of the planet became engulfed in ice.

“We capture that moment of entering an ice age in Scotland that is missing in all other localities in the world,” Prof Graham Shields of University College London, who led the research, told BBC News.

“Millions of critical years are missing in other places because of glacial erosion – but it is all there in the layers of rock in the Garvellachs.”

The islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland are uninhabited, apart from a team of scientists working out of the main island’s solitary building, although there are also the ruins of a 6th Century Celtic monastery.

The breakthrough was made by Prof Shield’s PhD student, Elias Rugen, whose results have been published in the Journal of the Geological Society of London. Elias is the first to date the rock layers and identify them as from the critical period that is missing from all other rock formations in all other parts of the world.

His discovery puts the Garvellachs in line for one of the biggest accolades in science: the golden spike hammered in at locations identified as the best record of planet-changing geological moments – though to ward off thieves the spike is not actually made of gold.

UCL

UCLElias has taken many of the judges of the golden spike, formally known as members of the “Cryogenian sub-commission”, several times to the rock faces to press his case.

The next stage is to allow the wider geological community to voice any objections or to come up with a better candidate. If there are none, then the spike could be hammered in next year.

The prize would raise the scientific profile of the location and attract further research funding.