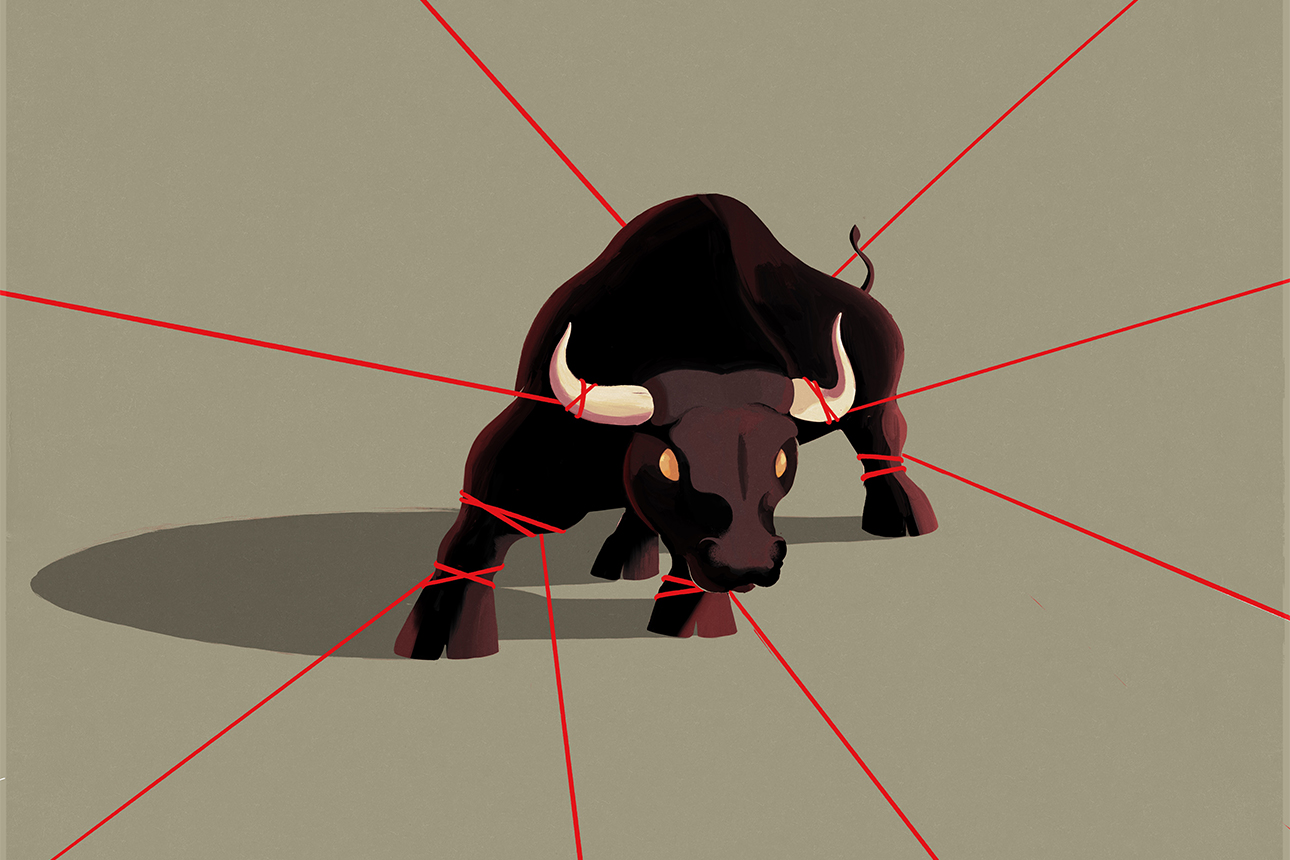

Record levels of share buybacks are attracting complaints from a growing number of prominent investors concerned that the practice is boosting executive bonuses but providing only limited benefits to shareholders.

The world’s 1,200 biggest public companies collectively bought back a record $1.3tn of their own shares last year, triple the level of a decade ago and almost as much as they paid out to shareholders in dividends, according to research by asset manager Janus Henderson. By contrast, total dividends have grown by just 54 per cent in the past 10 years.

The trend has continued this year, with new share purchases announced by companies including HSBC, Apple, Airbnb and caterer Compass. Oil was the sector with the largest amount of share buybacks last year, according to Janus Henderson; companies repurchased $135bn of their stock — four times as much as 2021.

Buybacks are a way for companies to return excess cash to shareholders, and can boost their share price, but the scale of the activity is increasingly attracting the interest of regulators.

US President Joe Biden introduced a 1 per cent tax on Wall Street buybacks that came into force in January; he has recently proposed to quadruple it.

The Securities and Exchange Commission recently approved a rule that will require publicly traded companies to disclose more information on their buybacks, such as the number purchased and average price paid.

“We would prefer buybacks to be less prevalent,” said Euan Munro, chief executive of Newton Investment Management.

“Used badly, [buybacks] can be used to manipulate [earnings per share] numbers upwards to meet medium-term management incentive targets at the expense of investments that might be important to a company’s long- term health,” he said.

Daniel Peris, a fund manager at Pittsburgh-based Federated Hermes, called buybacks an “environmental hazard”.

“The dividend is just the dividend: grandma benefits, the long-term holder [benefits]. Buybacks benefit traders, hedge funds, senior executives [and] near-term share prices.”

Leigh Himsworth, a UK equity fund manager at Fidelity, said: “As a shareholder you feel like you never actually get the reward” with buybacks. “If the market is nonplussed by it then, as a shareholder, you are worse than square one, as the company has typically used up their cash.”

Abrie Pretorius, a manager at Ninety One, said: “Buybacks only create value for remaining shareholders and strong relative performance when shares are cheap and there are no better uses of that cash which would generate higher returns. Most buybacks help optical [earnings per share] growth but destroy value.”

Buybacks also do not always translate into better share price performance. An Invesco fund that tracks the price of companies that do large buybacks has underperformed the US market over the past decade.

Share repurchases have traditionally been more common in the US stock market than in the UK or Europe, but they are on the rise worldwide. Between 2012 and 2022, repurchases by the biggest UK-listed companies more than tripled from $22bn to $70bn. US-listed companies increased buybacks from $333bn to $932bn, while in Europe share purchases more than doubled to $148bn.

“The approach we have seen in the US to generally prefer buybacks could be problematic if it takes root in the UK,” said Michael Stiasny, M&G’s head of UK equities. “The likely outcome would be that the market ends up yielding permanently less than it could.”

Nevertheless, some investors prefer buybacks to dividends, for instance because they may pay lower tax than on a dividend and can control the timing of when the tax is due.

“I don’t know how we’ve gotten to this point politically, but the idea that buybacks are a bad thing, or simply a way to manipulate your stock, I don’t think could be further from the truth,” said Jim Tierney, a portfolio manager at AllianceBernstein who focuses on growth stocks.

Lindsell Train co-founder Nick Train said that the benefit of buybacks depended on the purchase price, but they could be “a wonderful way for a board to build enhanced wealth for long-term shareholders”.

Bernard Ahkong, co-chief investment officer at UBS Asset Management’s hedge fund unit O’Connor, said: “We don’t want companies to boost dividends in an unsustainable fashion only to then have to cut them say one year later — and there would be less negative fallout from doing a one-off buyback, for example.”

On Friday, the US Chamber of Commerce sued the SEC in an effort to block its plan to require more buyback disclosure. “Stock buybacks play an important role in the functioning of healthy and efficient capital markets,” said Neil Bradley, the chamber’s vice-president and chief policy officer.

Some analysts expect the flurry of activity to taper off. Goldman Sachs forecasts that spending on buybacks by US S&P 500 companies will this year drop 15 per cent to $808bn and dividends will rise 5 per cent to $628bn as weak earnings growth constrains the total payout to investors, although next year it expects buybacks to rise again.

David Kostin, Goldman’s chief US equity strategist, said: “The slowdown in US earnings growth, the increase in policy uncertainty following the recent banking stress, and high starting valuations at which to repurchase stock all pose headwinds to buybacks.”

Sharp declines in US companies’ cash holdings have limited their ability to pursue buybacks, while rising interest rates have removed the incentive to fund them with debt, he said, adding that Biden’s buyback tax was unlikely to have a notable effect.

Additional reporting by Katie Martin and Laurence Fletcher

Record buyback spree attracts shareholder complaints