BBC

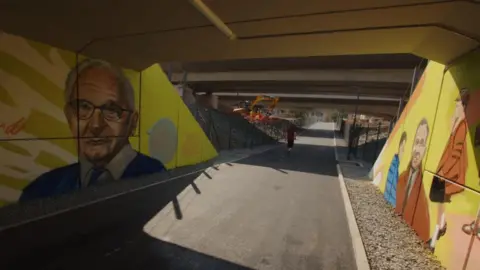

BBCA new street in Prague has been named after Sir Nicholas Winton, the British man who helped save hundreds of mostly Jewish children from the Nazis.

Four of them – now in their 80s and 90s – attended the ceremony for the street, which runs past a small train station from where tens of thousands of Czechoslovak Jews were deported during the Holocaust.

It coincided with the 85th anniversary of the last planned Kindertransport journey from Prague, which was prevented from departing due to the outbreak of World War Two.

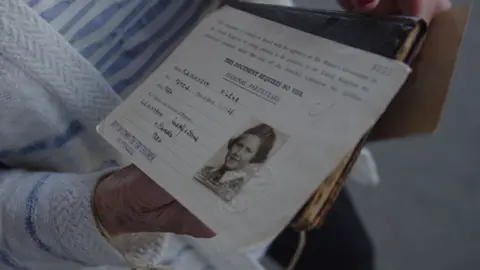

“This was my passport to freedom,” said Lady Milena Grenfell-Baines, clutching a document the size of a birthday card.

The card, slightly yellowed with age, showed that Milena Fleischmann (her maiden name), aged nine, was granted leave by His Majesty’s Government to enter the United Kingdom.

A photo of a cheerful girl wearing a smart, white-collared shirt was stuck to the front. The reverse was stamped with a swastika.

Clutching this document, and with a name tag hung around her neck, Milena travelled by train across Nazi Germany, watching over her three-year-old sister, Eva.

From there, they and dozens of other unaccompanied Jewish children crossed into Holland, before boarding a boat for England.

“We were all given cups of tea with milk. Nobody had ever had tea with milk. We all poured it out,” she said.

Eventually Milena and Eva were reunited with their parents, who also managed to escape. The Fleischmanns were the lucky ones. Many of their friends and relatives were not.

“I think it’s so important, because very soon, no eyewitnesses will be here anymore,” Milena, a youthful 94, told the BBC.

She spoke sitting on a chair on the same railway platform where tens of thousands of Czechoslovak Jews were herded onto trains bound for the Theresienstadt ghetto. Most would later be murdered at Auschwitz.

The station – Praha Bubny – has since been transformed into a memorial, and a much larger, modern station is being built nearby. A path for pedestrians and cyclists running beneath the tracks will from now on be known as Nicholas Winton Street.

“People need to remember why that street is called Nicholas Winton Street,” Milena went on. “Because there is a big generation – thanks to him – alive today.”

She and three other ‘children’ were brought to Prague to attend the ceremony organised by the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR).

“In remembering Sir Nicholas, we also honour the parents who sent away their children to an uncertain future, as well as the foster families who gave sanctuary to the youngest victims of Nazi oppression,” said Michael Newman, head of the AJR.

Family handout via Press Association

Family handout via Press Association“In today’s world, it’s really important that people don’t wait for someone else to initiate an act of goodness, but that they themselves start doing it,” Jan Cizinsky, mayor of Prague’s seventh district, told the BBC.

“It’s important that they take the first step, and then others will follow.”

Milena didn’t find out that the card – and therefore her survival – was largely the work of a 29-year-old British stockbroker until the 1980s, when the story appeared on the BBC programme That’s Life.

In now legendary footage, a speechless Winton was reunited with dozens of the then children he had helped to save in the final months before the outbreak of war.

In subsequent interviews he was always at pains to stress the operation was a team effort.

Apart from a month spent in Prague from Christmas 1938 to January 1939, most of the work – badgering politicians and diplomats, finding foster families, sometimes creating fake documents – was done from the safety of his home in London.

He was knighted in 2003 and died in 2015 at the age of 106.

Most of all, he remained haunted by the children he was unable to save.

Milena’s train was the eighth – and final – transport to leave occupied Prague.

A ninth – the largest, carrying some 250 children – was scheduled to leave on September 1st, 1939. But war intervened, and the train never left the station. All but a handful of the children are believed to have perished.