Family handout

Family handoutOn a Thursday afternoon towards the end of last month, a 59-year-old Palestinian woman set out to gather olives on her family’s land near the village of Faqqua, in the north of the occupied West Bank.

It was something that Hanan Abu Salameh had done for decades.

Within minutes, the mother of seven and grandmother of 14 lay dying in the dust of the olive grove, with a bullet wound in her chest – she’d been shot by an Israeli soldier.

Even though the family had co-ordinated their intention to pick olives with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), according to her son Fares and husband Hossam, the soldier fired several shots as other family members fled for cover.

The IDF says it’s investigating the incident, but Hanan’s grieving relatives have little hope or expectation that her killer will be brought to justice.

This wasn’t an isolated incident.

Harvesting olives is an age-old ritual and also an economic necessity for many Palestinians, but, according to the UN, it is increasingly precarious.

Farmers across the West Bank – internationally regarded as Palestinian land occupied by Israel – face heightened risks, like organised attacks by Israeli settlers seeking to sabotage the olive harvest, along with the use of force by Israeli security forces to block roads and Palestinians’ access to their lands.

“Last year we couldn’t even harvest our olives, except for a very small amount,” says Omar Tanatara, a farmer from the village of Umm Safa.

“At one point, the army came, threw the olives we’d already gathered on the ground, and ordered us to go home,” says Omar, who is also a member of the village council.

“Some people were even shot at and olives trees were cut down with saws – that’s how we later found them,” adds Omar, as he and other villagers use small hand-held rakes to pull this year’s harvest from their remaining trees while they can.

Even when Israeli and international activists accompany villagers to their olive groves, hoping to deter the threat, there’s no guarantee of safety.

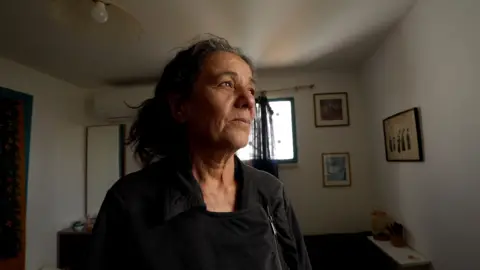

Zuraya Hadad instinctively winces as we watch a video of the incident in which her ribs were broken by a masked man wielding a large stick.

The Israeli peace activist had been helping Palestinian farmers pick their olives when she was assaulted without provocation.

Rather than arresting her attacker, Israeli soldiers, who’d accompanied settlers to the site, just told him to move on.

“Even when we come to help, it doesn’t guarantee that the Palestinians can harvest their olives,” Zuraya tells me as she recovers from her injuries at home.

“We try to raise awareness, but in the end it’s either the settlers steal the olives or cut the trees, or they remain unpicked and go to waste.”

Land is at the heart of the decades-old conflict between Israel and the Palestinians – who controls it and who has access to it.

For thousands of Palestinian families and villages, cultivating and harvesting olives is a big part of their economy.

But many say that, in recent times, access to trees on their land has been impeded, often violently by Israeli settlers.

Hundreds of trees – which can take years to reach fruit-bearing maturity – have been deliberately burned or cut down, says the UN.

More than 96,000 dunums (approximately 96 sq km; 37 sq miles) of olive groves in the West Bank also went uncultivated in 2023 because of Israeli restrictions on access for Palestinian farmers.

After being gathered by hand, villagers from Umm Safa take sacks full of olives to the nearby factory, where the presses have restarted this season.

Olives are the most important agricultural product in the West Bank. In a good year, they’re worth more than $70m (£54m) to the Palestinian economy.

But income was well down last year and this year will be even worse, says factory owner Abd al-Rahman Khalifa, as even fewer farmers are able to harvest their crop owing to attacks by settlers.

“Let me give you an example,” he tells me.

“My brother-in-law in Lubban – next to the Israeli settlement – went to pick his own olives, but they broke his arms and they made him leave along with everyone who was with him.”

“We, as Palestinians, don’t have petrol or big companies. Our main agricultural crop is olives,” he adds. “So, like the Gulf depends on oil, and the Americans on business, our economy is dependent on the olive tree.”

On the hill overlooking the olive groves of Umm Safa stands an illegal settler outpost – a farm.

The extremist settler who runs it, Zvi Bar Yosef, was sanctioned this year by the UK and other Western governments for repeated acts of violence against Palestinians, including twice threatening families at gunpoint.

Over the last year of the war in Gaza, Jewish settlers have been emboldened by the support of far-right Israeli ministers like Itamar Ben-Gvir.

As national security minister, he has given out free firearms to hundreds of settlers and has encouraged them to assert their right to what – they say – is their “God-given” land.

Ben-Gvir has also been accused of openly supporting the disruption of olive harvesting on Palestinian land.

At the olive press, farmers wait patiently in the yard to witness the transformation of the olives they’ve been able to gather this year into “liquid gold”.

The olive tree has been a symbol of this land for centuries.

For generations of Palestinians, it is their link to the land – a link that is under threat now more than ever.