BBC

BBCWhen a white van drew up next to the office of the Palestine Customs Police in Tubas, a town in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Abdel Nasser Sarhan had no reason to be suspicious.

According to Abdel Nasser’s colleagues, the van’s driver got out and greeted him in Arabic.

It was early in the morning. The 24-year-old uniformed policeman had just come on shift.

CCTV pictures show him strolling out past a guard post, his rifle slung casually at his side.

Seconds later, a man in jeans and a dark T-shirt emerges from the direction of the white van, uniformed Israeli soldiers behind him.

He raises a handgun and shoots Abdel Nasser dead.

Soon, the street is full of Israeli soldiers. They retrieve Abdel Nasser’s rifle and, as his colleagues try to retrieve his body, continue to shoot – all captured on CCTV.

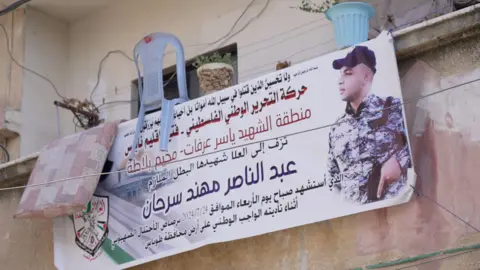

When we visited Tubas the following morning, in late July, we found a makeshift memorial of stones and wilting flowers on the ground where Abdel Nasser fell.

The guard post and adjacent walls were riddled with bullet holes, each marked with a yellow tag. Fading bloodstains smeared the ground and doorway.

In a statement released on the day of the incident, the Israeli army said the shooting occurred in the course of an operation to detain two wanted men.

Abdel Nasser’s colleagues in Tubas said those arrests took place at a nearby house.

The army said that soldiers had “encountered armed terrorists” and that “a customs officer of the Palestinian Authority was killed during exchanges of fire”.

From the evidence of the CCTV footage, this last statement is demonstrably false.

An Israeli security official contacted by the BBC two weeks later said the incident was “one of hundreds, if not thousands of special activities that are planned and carried out very precisely”.

This one was being reviewed, he said, “because it didn’t go as planned”.

It seems clear that this was an operation that went badly wrong.

No-one has suggested that Abdel Nasser or the customs office were the target of the operation.

The young guard appears to have had the misfortune to stumble across an undercover Israeli operation, during which he was shot and killed.

Reuters

ReutersBut for Abdel Nasser’s colleagues in the customs police, this tragic episode is part of a wider pattern of behaviour that is making it harder than ever for the Palestinian Authority – theoretically responsible for security in areas not under direct Israeli military control – to do its job.

“This rings a warning bell, especially for us in the security services,” Lt Ibrahim Ayyash, spokesman for the Palestine Customs Police, told us.

“How can we enforce law and order and offer services to the people and protect them while you’re obstructing my work and killing my officers?”

Customs officers, he said, were increasingly reluctant to pull over suspicious vehicles, for fear of stumbling across Israeli soldiers operating under cover.

“It now falls on you, as a custom officer, to take a decision about stopping a vehicle or not,” he said.

“If you stop it and it has Special Forces [inside], they could kill you.”

As fans of the Israeli TV show Fauda will know, undercover operations were already a regular feature of life in the West Bank long before the war in Gaza broke out last October.

Recent evidence suggests the frequency of such operations have increased, with multiple cases of CCTV pictures showing Israeli units, dressed as civilians, and even medics, snatching wanted Palestinians from city streets and hospital beds.

But such clandestine operations are part of a much bigger picture.

With all eyes focused on Gaza, another war is raging in the West Bank, as the Israeli military cracks down on armed groups that it says are being bankrolled by Iran.

“The situation on the ground is very, very complicated,” an Israeli security official told me, on condition of anonymity.

“You might say that it’s on the verge of an explosion.”

The emergence of a new generation of local armed groups, mostly in the refugee camps of the northern West Bank, dates back to about 2021, with the first group appearing in Jenin.

But the war in Gaza has fanned the flames of rebellion in other cities, from Tulkarem to Qalqilya and, more recently, Tubas.

Israel’s security crackdown, the actions of violent groups of Jewish settlers and the belief that the Palestinian Authority is powerless to protect them have all added to an atmosphere of mounting tension.

“They’re very frustrated with Israel, they’re very frustrated with the Palestinian Authority and they’re looking for an outlet to this frustration,” the Israeli security official said.

The PA health ministry says more than 600 Palestinians have been killed in the West Bank since last October. As many as 10,000 have been arrested, according to the Palestinian Prisoners Society.

At least 17 Israelis, including 12 security forces personnel, have also been killed in the West Bank, according to a UN tally.

Some veteran observers fear that armed clashes could erupt into a full-scale uprising, or intifada.

“If it goes into an intifada, this is a much, much bigger problem,” Gen Israel Ziv, former head of the IDF’s Operations Division, told me.

“Militarily, we handle things better or worse. But when it goes into an intifada, it’s a totally different story. And it might go there.”

With the Israeli military still focused on the war in Gaza and its simmering conflict with Hezbollah along its northern border, Gen Ziv said there’s reluctance to recognise danger much closer to home.

“It’s a huge problem that can blow up in our face in a more sensitive area, [close] to the centres of population in Israel,” he said.

Meanwhile, in the Balata refugee camp, on the edge of Nablus, Abdel Nasser’s family is still grieving.

They’ve watched the CCTV pictures from Tubas and drawn their own conclusions about the actions of the Israeli army.

“He come to kill, just to kill,” Abdel Nasser’s uncle, Ismail Mohammed Sarhan, says.

Abdel Nasser’s father, Mohannad, can barely comprehend the loss of his son.

What was he like, I asked him.

“Ambitious, kind, always smiling,” he said, unable to hold back the tears.