TV BRA

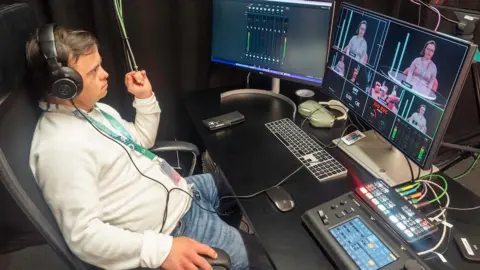

TV BRAIt’s perhaps no surprise that the décor of TV BRA’s new studio is shocking pink.

It’s the favourite colour of two of the station’s reporters, Emily Ann Riedel – who is wearing a pink top when I visit – and Petter Bjørkmo. “I even had pink hair!” Bjørkmo tells me, laughing, before adding that he had to get rid of it “because I am a reporter – reporters have to look decent.”

All the reporters at TV BRA – which means “TV Good” – are disabled or autistic; most have a learning disability.

Every week, they put together an hour-long magazine programme covering news, entertainment and sport, which is broadcast on a major Norwegian streaming platform, TV2 play, as well as TV BRA’s own app and website.

‘I have inner beauty and outside beauty’

The show is presented in simple Norwegian and is slower than mainstream news reports, making it much easier to follow. Between 4,000 and 5,000 people tune in every week.

The station’s 10 reporters are dotted around the country, where they work as local news correspondents.

Riedel, who has Down’s Syndrome, lives and works in the seaside city of Stavanger. She has had to learn to contain her effusive personality.

“I have to follow the script and not talk about personal stuff – because here is about the news. When I work here I have to be very professional.”

Although she has been at the station for years, some things are still novel, like the mascara she wears before going on camera, and which she says weighs down her eyelids.

“I don’t need it because I look beautiful,” Riedel tells me with a smile. “I have inner beauty and outside beauty.”

“Yeah that’s right,” chuckles Camilla Kvalheim, the managing editor of the station – and also, currently, make-up artist. “But in the studio, with heavy lights and everything, you look paler.”

Kvalheim and a small technical crew who are not disabled produce and edit all the reports.

Although Riedel and her colleagues have mild learning impairments – they can mostly speak English well, and travel without support – some things are a challenge.

I watch as the team tries to get to grips with a new autocue system. The presenters frequently have to read a line many times to get a good take.

“Sometimes it can be difficult to say what’s in the cue cards, so we have to do it again and again,” says Kvalheim. She also has to provide on-the-job training for her team, who did not study journalism at university before joining the TV station.

Nevertheless her expectations of her team are high.

“She says: ‘Can you please do that again? Can you repeat what you said? Can you look directly into the camera, I want you to be perfect – this is very important,’” says Riedel.

“And when she is being proud, when we are finished, then she says: ‘I like this part! I like this part! That is what I want to see! Use your energy to be the best that you can be!’”

It’s been pointed out that people with learning disabilities can be held back by overly positive feedback, which stops them from developing their skills. That is not an issue here.

“If we are going to be seen by the audience we have to have a professional look,” says Kvalheim unapologetically. “If they are going to be respected as reporters and journalists they need to follow the ethical standards of other news organisations.”

The origins of TV BRA began more than a decade ago, when she was working as a teacher for people with a learning disability at a residential care home in Bergen, and decided to pursue a passion for filmmaking. She found that as soon as she got a camera out, the dynamic between her and the people she was working with changed.

“Suddenly when we were working together on those films, we were a crew, we were a team. It wasn’t me over them – we were equal,” Kvalheim recalls.

Finding that her creative collaborators had much to say about the world, she was encouraged to continue the work, and it steadily built momentum.

Now it is a national network, with a proper studio – but Kvalheim admits that her reporters are not paid the same sort of money as their peers at other networks.

The station receives state funding, and has revenue from supplying TV2 with a weekly show, but money is extremely tight.

A good job, then, that the team are motivated by things other than money. In Norway, as in every country, people with learning disabilities face issues ranging from low employment rates to access to support and housing. Being able to understand the news empowers the wider community to campaign on these issues.

‘Talking about rights’

A recent report from Petter Bjørkmo is a case in point. He visited a woman with more severe learning disabilities, who lives in sheltered accommodation in Trondheim. “The city – the government – wants to take away her shopping,” he told me, meaning her budget to be accompanied to the shops by a support worker.

“They told her that she has to go online. But she can’t! Because she can’t speak very well, it’s hard for her to get online to buy food. She needs help!”

Bjørkmo’s report a got a “massive response” from viewers, says Kvalheim, though it did not cause the local government to rethink their position.

“TV BRA is very important,” agrees Svein Andre Hofsø, another reporter. “Because we are talking about people with a disability, and what are our rights in real life.”

Hofsø, a roving news reporter based in Oslo, was well-known even before joining TV BRA.

He took the title role in a 2013 film, Detective Downs. Before the last parliamentary election, in 2021, Andre got the chance to don his detective’s fedora again, but this time his job was to grill various politicians on their policies in his tongue-in-cheek style.

One such sequence shows him sitting on a bench outside the parliament building in Oslo, pretending to read a newspaper. A politician, Jonas Gahr Støre – the leader of the Labour Party – strolls outside but behind a pillar, a stooge is waiting to ambush him. As Hofsø looks on, the stooge throws a butterfly net over the unsuspecting Støre.

In the next scene, we see Støre in a chair in a basement. Hofsø shines an angle-poised lamp in his face, and shows him photos of disabled people looking sad and lonely. “If we vote for you, what will you do for us?”

At this point, Støre sets out his policies for disabled people. And after the election, he did indeed become prime minister.

Camilla Kvalheim laughs when she recalls the encounter. “That was very funny. Every time we’ve met him since, he says, ‘Oh – are you going to catch me in that butterfly net?!’”

On the day I visit TV BRA, they are paid a visit from Silje Hjemdal, a local lawmaker for the right-wing Progress Party.

A team of four reporters quiz her on everything from roads to immigration, and what she thinks of plans for the lavish new national theatre in Oslo (being from Bergen, she has some doubts about the project). Kvalheim is there too, steering the questions.

Hjemdal’s answers are serious, but there is also a warmth to the encounter; she is a long-term supporter of the station .“A lot of politicians now know what TV BRA is, so I would say it’s a big, big progress, just the five last years,” she tells me.

‘Making TV in a new way’

TV BRA is not the only TV news station presented by people with learning disabilities. Similar, albeit smaller, programmes exist in Iceland and Denmark. Meanwhile Slovenia, Holland and several other countries offer an “easy news” service – simplified reports, though not presented by people with a learning disability.

For viewers of TV BRA, this kind of service is essential. “I think this TV station is really important for our community,” says Anne-Britt Ekerhovd, a fan of the station, who has a learning disability. “They explain things really well. In different news like NRK, they explain it too hard for us to understand. TV BRA is much easier to understand.”

Another fan of the station, Espen Giertsen, agrees: “There is something special about this – they are making TV in a new way.”

TV BRA’s reporters are very conscious of the important role they have in serving this often-neglected audience.

“If they have tonnes of weight on themselves, I want them to lift it up, so they can be free, so they can feel like they are accepted,” says Emily Ann Riedel.

People Fixing the World – The pioneering TV news service

TV BRA in Norway is a unique media organisation. Their fortnightly national news show is presented by reporters who have learning disabilities or are autistic.

Through interviews with politicians and other authority figures the station aims to hold the powerful to account, while also changing the way that people with learning disabilities are seen.

Our reporter William Kremer join them in their flashy new studio in Bergen where the journalists share some of their best stories and tell us about their aspirations for the future.