Lik family

Lik familyClutching a toothbrush and toothpaste, Kevin Lik waited for six hours in the main office of penal colony 14, near Arkhangelsk in Russia’s far north-west. It was late in the evening of Sunday 28 July, and the 19-year-old says he had no idea what was about to happen.

“Maybe you’re taking me to be shot,” he said to the governor of the colony.

“Don’t worry, everything will be fine,” came the reply.

Kevin says he was told the same thing by an officer from Russia’s FSB state security agency a year and a half ago, before they locked him up.

“I lost a lot of weight in the colony,” he explains shyly, as we speak on a video call. Kevin is about 6ft 4in tall (1.9m) but weighs only 11 stone (70kg).

Along with American journalist Evan Gershkovich, he is one of 16 people released by Russia on 1 August in a prisoner swap with the US and other Western countries.

Lik family

Lik familyThe teenager – with dual Russian and German citizenship – was arrested last year while still at school and became the youngest person in modern Russian history to have been convicted of treason.

I ask if he considers himself more Russian or German. “It’s a very complicated question,” he replies.

Kevin was born in 2005 in Montabaur, a small town in the west of Germany. His Russian mother, Victoria, had married a German citizen and, although the marriage didn’t last, she and her son stayed.

They visited Russia every couple of years until Victoria decided she wanted to go back permanently – she missed her relatives and hometown of Maykop in the North Caucasus. Kevin was 12 when they made the move there in 2017.

They lived on the outskirts of town, in an apartment with views of mountains and a military base. Kevin says he loved walks in the countryside and collecting plants for his herbarium, and also studying at school.

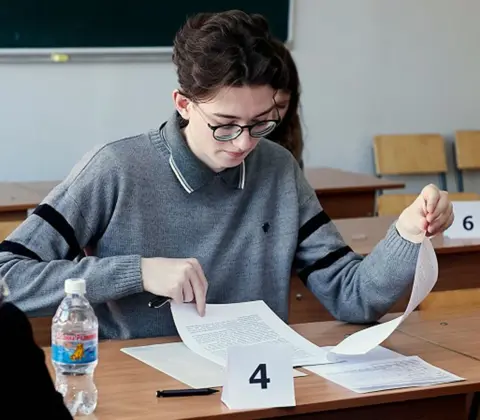

Lik family

Lik family He enthusiastically shows me certificates from national and local academic competitions that he won.

It was the 2018 Russian presidential election that sparked his interest in politics, he says. His mother – a public sector healthcare worker – would come home and say she and her colleagues had been bussed to polling stations where they were told: “Vote for Putin, or we’ll take away your bonus.”

He was only 12 at the time, but says he understood “there was almost no democracy in Russia”.

Kevin was enraged that almost every classroom in his school had a portrait of Putin.

“They constantly told us that school is not a place for politics. It’s just not right to hang portraits and promote a personality cult like that,” he says.

Adyghe State University

Adyghe State UniversityA year or so later, he caused a scandal when he swapped a school portrait of Putin for one of opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

“One teacher said that during Stalin’s time, I would have been shot,” Kevin recalls – while a sympathetic teacher, he says, advised him to be careful.

His mother was called to the school: “They scolded her, yelled at her,” he says.

The BBC has asked the school for comment, but has not had a response.

Pizza but no handcuffs

As Kevin approached his final school year, his mother decided they should move back to Germany.

By this time, Russia had invaded Ukraine and, in order to leave the country permanently, Kevin’s name had to be removed from the military register.

Victoria was invited to the enlistment office to sort out her son’s paperwork. When she got there on 9 February 2023, the police met her. Kevin says they groundlessly accused her of swearing in public. She was sentenced to 10 days’ detention, which meant they had to delay their plans to leave.

Left alone, Kevin stopped going to school. He ventured out for a few hours one day, and says that when he returned to the apartment “things had been moved around”.

FSB

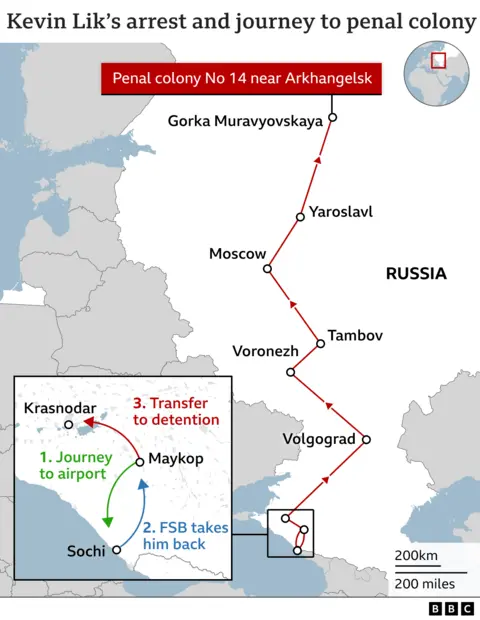

FSBWhen Victoria was released, they tried to get to Germany by heading south to the city of Sochi, which has an international airport. After checking into a hotel, Kevin says they went out for a snack and he noticed a man in a medical mask and hoodie filming them on his phone. Within seconds, he says a minibus pulled up.

“Eight or nine FSB officers jumped out. One grabbed me by the arm. Another came up, showed his ID, and said: ‘A criminal case has been opened against you under article 275: treason.’

“My eyes were wide with shock.”

The minibus took them to the hotel, where they collected their luggage. On the way back to Maykop they were put in a car without licence plates and taken to a pizzeria.

“They ordered pizza and offered us some. They didn’t handcuff me or restrain me. I was thinking everything over in my head but couldn’t understand how I had committed treason,” says Kevin.

He asked if he would be put in jail. “Don’t worry, everything will be fine,” came the response.

Kevin remembered a former FSB operative, Vadim Krasikov, who was serving a life sentence in Germany for killing a man in Berlin on Kremlin orders. He started wondering if Russia planned to use him – a German citizen – “as a hostage” to get Krasikov back.

‘It’s a chess game – there was no justice’

They got home in the middle of the night. He shows me the video FSB officers made as they searched the apartment. They found a broken telescope – an old birthday present from his mother.

The authorities suspected he had used it to photograph military vehicles from his window to send to German intelligence. They took his phone and laptop and found pictures of the base.

FSB

FSBKevin freely admits he took the photos but says he had no intention of passing them on to anyone.

At 03:00, Kevin was taken to the local FSB building for interrogation. Because he was only 17, his mother went with him. He was scared.

Kevin says the lawyer assigned to him told him straight away that he should confess to reduce the sentence.

As we speak, he reels off details of Russia’s criminal code and uses legal terms to explain why he was wrongfully accused. But, back then, he had no idea how to handle the situation.

FSB

FSBA confession had already been typed and Kevin agreed to sign it, which he later regretted. He says he was afraid if he didn’t sign, things would have “got worse because they could have started pressuring my mum”. The FSB investigator told them he had the power to seize their apartment, says Kevin.

“The testimony was absolute nonsense,” he says. “It’s a chess game, it was clear there was no justice.”

Because he was still a minor, he was taken to a special facility two hours’ drive away in Krasnodar and placed in a solitary cell. He had been up all night but couldn’t sleep.

“They brought me food but I couldn’t eat it. I really wanted to see my mum.”

A few months later, when he turned 18, he was moved to a different prison on the outskirts of Krasnodar where he mixed with other inmates.

Kevin says he was left terrified after a group of inmates beat him up. “They tied my hands, beat me, and even put out a cigarette on me. They hit me so hard in the chest I couldn’t breathe.”

Lik family

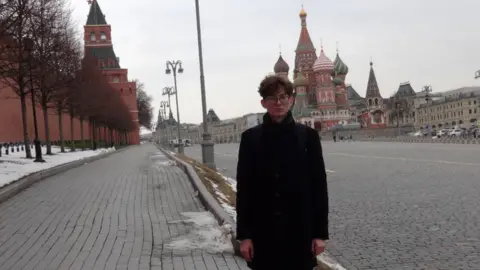

Lik familyAll this time, the authorities continued to investigate him. His class teacher testified against him, claiming that when they had gone to an academic competition in Moscow Kevin had wanted to go to the German embassy to contact intelligence officers. Kevin tells me all he wanted was to get an official German ID, because he had turned 16.

A Ministry of Defence expert analysed the photos Kevin had taken and concluded they didn’t constitute a state secret but, in foreign hands, could have harmed Russia.

The FSB file on him also included details of childhood trips to Russia, including one when he was two years old. Kevin says he also found out his phone had been tapped as early as 2021.

Ten months after Kevin’s arrest, at the end of December 2023, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to four years in a penal colony.

FSB

FSBApart from his mum, no-one he knew from Maykop contacted him after his arrest, but after the media reported his case, strangers began writing.

“The letters helped me a lot,” he says. “On my birthday, I received 60 cards. I made it my goal to reply to each person.”

The letters and cards were later confiscated.

Kevin’s journey to the penal colony in Arkhangelsk took a month, via several other prisons. He arrived there at the end of June this year. In those following weeks, he says he passed the time by reading and studying.

‘Too good to be true’

Suddenly, as he was leaving the bath house on Tuesday 23 July, he was approached by a senior prison officer and told he had 20 minutes to “urgently write a petition” for a presidential pardon, which he did.

Then, on the 28th, a prison officer stopped him and told him to get his toothbrush, toothpaste and slippers.

“Usually, you get this kit when they’re about to put you in the punishment cell,” explains Kevin. But instead, he was locked in an office.

At 01:00 on the morning of Monday 29th, a convoy arrived to take him away.

The thought of being exchanged was at the back of Kevin’s mind, but seemed too good to be true.

He was flown to Moscow, where he was kept in jail until Thursday 1 August, when he was put on a plane with the other prisoners who were being swapped.

It was never spelled out to him that he was being exchanged, he says, but by the time he was in the air bound for Turkey it was clear what was happening.

As Kevin had long-suspected, assassin Vadim Krasikov was among those being returned to Russia.

In Germany, after a hospital check-up, Kevin was finally able to greet his mother, who had got a visa to fly in from Russia.

“She cried. I told her everything was fine, not to worry, that I loved her very much.”

Mother and son are now living in Germany and Kevin is full of enthusiasm to finish school.

“I don’t have a desire for revenge, but I do have a very strong desire to participate in opposition activities,” he tells me.

Kevin still has his prison uniform, stuffed in a bag in the corner of his room.

When I ask what he wanted most of all while he was forced to wear it, he simply replies: “To hug Mum of course.”