BBC

BBCWe are surrounded by an invisible killer. One so common that we barely notice it shortening our lives.

It’s causing heart attacks, type 2 diabetes and studies now even link it to dementia.

What do you think it could be?

The answer is noise – and its impact on the human body goes far beyond damaging hearing.

“It is a public health crisis, we’ve got huge numbers of people exposed in their everyday life,” says Prof Charlotte Clark, from St George’s, University of London.

It’s just a crisis we don’t talk about.

So I’ve been investigating when noise becomes dangerous, chatting to the people whose health is suffering and seeing if there’s any way of overcoming our noisy world.

I started by meeting Prof Clark in an eerily silent sound laboratory. We’re going to see how my body reacts to noise and I’ve been kitted out with a device that looks like a chunky smartwatch.

It’s going to measure my heart rate and how much my skin sweats.

You can join in too if you have some headphones. Think about how these five sounds make you feel.

The one I find really grating is the traffic noise from Dhaka, Bangladesh, which has the title of the noisiest city in the world. I immediately feel like I’m in a ginormous, stressful traffic jam.

And the sensors are picking up my agitation – my heart rate shoots up and my skin is sweating more.

“There’s really good evidence that traffic noise affects your heart health,” says Prof Clark, as the next sound is prepared.

Only the joyful sounds of the playground have a calming effect on my body. The dogs barking and the neighbour’s party in the early hours lead to a negative response.

But why is sound changing my body?

“You have an emotional response to sound,” says Prof Clark.

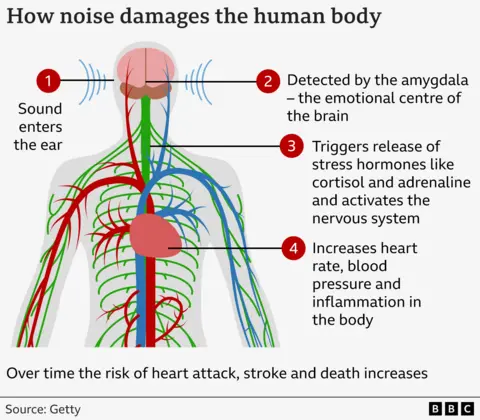

Sound is detected by the ear and passed onto the brain and one region – the amygdala – performs the emotional assessment.

This is part of the body’s fight-or-flight response that has evolved to help us react quickly to the sounds like a predator crashing through the bushes.

“So your heart rate goes up, your nervous system starts to kick in and you release stress hormones,” Prof Clark tells me.

All of this is good in an emergency, but over time it starts to cause damage.

“If you’re exposed for several years, your body’s reacting like that all the time, it increases your risk of developing things like heart attacks, high blood pressure, stroke and type 2 diabetes,” says Prof Clark.

Insidiously, this even happens while we’re fast asleep. You might think you adapt to noise. I thought I did when I lived in a rental near an airport. But the biology tells a different story.

“You never turn your ears off; when you’re asleep, you’re still listening. So those responses, like your heart rate going up, that’s happening whilst you’re asleep,” adds Prof Clark.

Noise is unwanted sound. Transport – traffic, trains and aeroplanes – are a major source, but so too are the sounds of us having a good time. One person’s great party is another’s insufferable noise.

I meet Coco at her fourth-floor flat in the historic Vila de Gràcia area of Barcelona, Spain.

There’s a bag of freshly picked lemons tied to her door gifted by one neighbour, her fridge contains a tortilla cooked by another and she offers me fancy cakes made by a third neighbour who’s training in patisserie.

From the balcony you can see the city’s famous cathedral, the Sagrada Familia. It is easy to see why Coco has fallen in love with living here, but it comes at a huge price and she thinks she’ll be forced to leave.

“It’s extremely noisy… it’s 24-hour noise,” she tells me. There’s a dog park for owners to walk their pooches which “bark at 2, 3, 4, 5am” and the courtyard is a public space that is used for everything from children’s birthday parties to all-day concerts finished off with fireworks.

She gets out her phone and plays the recordings of the music being blasted out so loud it makes the glass in her windows vibrate.

Her home should be a refuge from the stress of work, but the noise “brings frustration, I feel like crying”.

She has been “hospitalised twice with chest pain” and “absolutely” thinks noise is causing the stress, which is damaging her health. “There is a physical change that I feel, it does something to your body, for certain,” she says.

In Barcelona there are an estimated 300 heart attacks and 30 deaths a year just from traffic noise, according to researcher Dr Maria Foraster, who has reviewed evidence on noise for the World Health Organization.

Across Europe noise is linked to 12,000 early deaths a year as well as millions of cases of severely disturbed sleep as well as serious noise annoyance which can impact mental health.

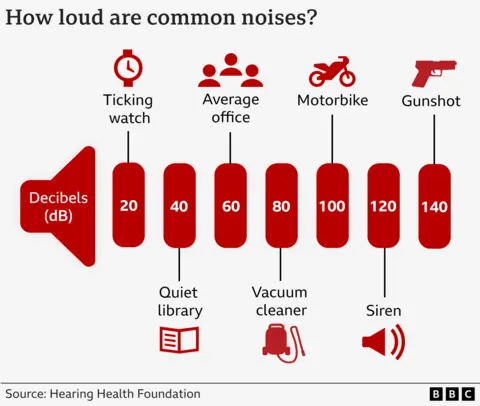

I meet Dr Foraster at a café that is separated from one of Barcelona’s busiest roads by a small park. My sound meter says the noise from the distant traffic is just over 60 decibels here.

We can easily chat over the noise without raising our voices, but this is already an unhealthy volume.

The crucial number for heart health is 53 decibels, she tells me, and the higher you go the greater the health risks.

“This 53 means that we need to be in a rather quiet environment,” says Dr Foraster.

And that’s just in daytime, we need even lower levels for sleep. “At night we need quietness,” she says.

Although it is not just about the volume, how disruptive the sound is and how much control you have over it affect our emotional response to noise.

Dr Foraster argues the health impact of noise is “at the level of air pollution” but is much harder to comprehend.

“We are used to understanding that chemicals can affect health and they are toxic, but it’s not so straightforward to understand that a physical factor, like noise, affects our health beyond our hearing,” she says.

A loud party can be the fun that makes life worth living and someone else’s intolerable noise.

The sound of traffic has the greatest impact on health because so many people are exposed to it. But traffic is also the sound of getting to work, doing the shopping and taking the children to school. Tackling noise means asking people to live their lives differently – which creates problems of its own.

Dr Natalie Mueller, from the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, takes me for a walk around the city centre. We start on a busy road – my sound meter clocks in at over 80 decibels – and we head to a quiet tree-lined avenue where the noise is down to the 50s.

But there is something different about this street – it used to be a busy road, but the space was given over to pedestrians, cafes and gardens. I can see the ghost of an old cross roads by the shape of the flowerbeds. Vehicles can still come down here, just slowly.

Remember earlier in the lab, we found that some sounds can soothe the body.

“It is not completely silent, but it’s a different perception of sound and noise,” Dr Mueller says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe initial plan was to create more than 500 areas like this, termed “superblocks” – pedestrian-friendly areas created by grouping several city blocks together.

Dr Mueller performed the research projecting a 5-10% reduction in noise in the city, which would prevent about “150 premature deaths” from noise alone each year. And that would be “just the tip of the iceberg” of the health benefits.

But in reality only six superblocks were ever built. The city council declined to comment.

Urbanisation

The dangers of noise though are continuing to grow. Urbanisation is putting more people into noisy cities.

Dhaka, Bangladesh, is one of the fastest growing megacities in the world. This has brought more traffic and given the city a cacophonous soundtrack of honking horns.

Artist Momina Raman Royal earned the label of the “lone hero” as his silent protests have focused attention on the city’s noise problem.

For about 10 minutes each day, he stands at the intersection of a couple of busy roads with a big yellow placard accusing drivers who honk their horns loudly of causing a massive nuisance.

He took on the mission after his daughter was born. “I want to stop all honking from not only Dhaka, but from Bangladesh,” he says.

“If you see the birds or trees or rivers, no one’s making noise without humans, so humans are responsible.”

But here there are the beginnings of political action too. Syeda Rizwana Hasan, who’s the environment adviser and minister for the government of Bangladesh, told me she was “very worried” about the health impacts of noise.

There is a crackdown on honking horns to get the noise levels down – with an awareness campaign and stricter enforcement of existing laws.

She said: “It’s impossible to get it done in one year or two years, but I think it is possible to ensure that the city becomes less noisy, and when people feel that, they feel better when it’s less noisy, I’m sure their habit will also change.”

The solutions to noise can be difficult, complicated and challenging to solve.

What I’m left with is a new appreciation for finding some space in our lives to just escape the noise because in the words of Dr Masrur Abdul Quader, from the Bangladesh University of Professionals, it is “a silent killer and a slow poison”.

LOUD was produced by Gerry Holt. Additional reporting from Bangladesh by Salman Saeed