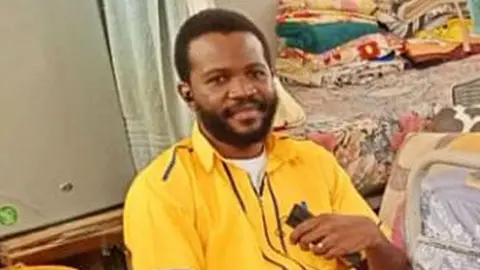

Stanis Bujakera

Stanis BujakeraIn attempting to describe Makala Prison – the scene of a deadly and failed breakout this week in the Democratic Republic of Congo – two people who have been inside used the exact same word: “hell”.

“Makala is a true hell,” Stanis Bujakera, a former inmate and journalist, told the BBC about DR Congo’s largest jail.

Bujakera was sent to the notorious Makala Prison in September last year, after the authorities accused him of writing an article that alleged the military were involved in an opposition politician’s death. He spent six months there.

“Makala is not a prison, but a detention centre resembling a concentration camp, where people are sent to die,” he said.

The prison, located in capital city Kinshasa, has a capacity of 1,500 prisoners but is estimated to hold around 10 times more.

This cramped population ranges from petty criminals to political prisoners to murderers.

Human rights groups have long complained of the dire conditions Makala inmates face, including overcrowding, unsubstantial food and poor access to clean water.

Following a disaster at the facility earlier this week, these conditions have been thrust into the spotlight once again.

After masses of inmates tried to break out of Makala in the early hours of Monday morning, 129 prisoners lost their lives, Interior Minister Jacquemain Shabani said.

Two dozen were shot dead as they tried to escape, Mr Shabani reported, but most were suffocated in a crush.

EPA

EPAFour surviving inmates told the New York Times that prior to the escape attempt, prisoners had been held in stifling cells without running water or the electricity to power fans for more than a day-and-a-half.

Some prisoners had initially broken out to escape the heat, they said.

Bujakera said these conditions were far from unusual – taps “constantly” run dry at Makala, while “electricity is random, leaving the detainees without light for days on end”.

“Inmates are literally abandoned to their fate, exposed to overcrowded and unsanitary conditions that foster contamination and the spread of disease,” he added.

Prisoners die “every day” as a result, Bujakera said.

Rostin Manketa, executive director of Congolese human rights group La Voix des Sans Voix, shares a similar account.

He has visited Makala several times and concluded that when a person has been sent to Makala Prison, “it seems like [they] have been sent to hell”.

Stark videos filmed by Bujakera during his time in Makala show dozens of sleeping men, packed tightly together on the floor of an overflowing room.

Their limbs overlap, and in a delicate balancing act some men sleep atop the walls that divide shower stalls.

Stanis Bujakera

Stanis BujakeraConditions are better in Makala’s VIP section, a separate pavilion that only the minority can afford – you get a bed and more space, for example.

Bujakera was asked the pay $3,000 (£2,280) to stay in VIP, but he managed to get this price slashed to $450 (£340) for his stay.

He told the BBC: “Economic inequalities between inmates create a hierarchy… the poorest are abandoned to their fate.”

What is more, wardens at Makala have little presence. Law and order inside the prison is effectively delegated to the inmates themselves.

“Prisoners govern themselves,” Fred Bauma, a human rights activist who was incarcerated in Makala from March 2015 to August 2016, told BBC’s Focus on Africa podcast this week.

“It’s like you’ve changed countries and there’s a new government and you need to learn those rules.”

This system of self-government is dysfunctional and leads to “harmful power dynamics, acts of violence and conflicts between inmates”, Bujakera said.

But Makala is not alone with its abysmal conditions – prisons all over the country are chronically underfunded and overcrowded.

According to the World Prison Brief project, DR Congo’s jails are the sixth-most overcrowded globally.

The authorities have acknowledged this problem on a number of occasions. Following Monday’s jailbreak, Deputy Justice Minister Samuel Mbemba blamed magistrates for prison overcrowding, noting that “even mere suspects are sent to prison”.

Many inmates have not actually been sentenced for a crime but are instead held in jail for months – or years – while waiting to be tried.

The food in DR Congo’s prisons has also been criticised widely.

In Makala, inmates get only one meal per day – and this dish is often of limited nutritional value.

Pictures taken by Bujakera show a tub of maize meal – a staple carbohydrate in DR Congo – turned hard and dry, accompanied by a watery brown vegetable stew.

Stanis Bujakera

Stanis BujakeraIn order to avoid malnourishment, many prisoners rely on their relatives to bring food into them.

However, not everyone has these connections.

In 2017, a charity reported that at least 17 prisoners starved to death following food shortages in Makala.

Mr Manketa said it was “possible” that Makala’s testing environment led to the tragic attempt to escape.

To avoid a repeat, the authorities should build new prisons and improve existing ones, he argues.

Bujakera, who is now based in the United States, said this change must happen swiftly.

It is a “sick” justice system, he lamented, and as Monday’s disaster demonstrated, people are dying while waiting for a cure.

Additional reporting by the BBC’s Emery Makumeno in Kinshasa.

More BBC stories from DR Congo:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC