National digital reporter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPresident Donald Trump has always understood the power of branding. As a celebrity businessman, he affixed his name to the facades of his skyscrapers and licensed his name to an array of products, from hotels to wines.

Now, he is attempting his boldest branding campaign yet: America itself.

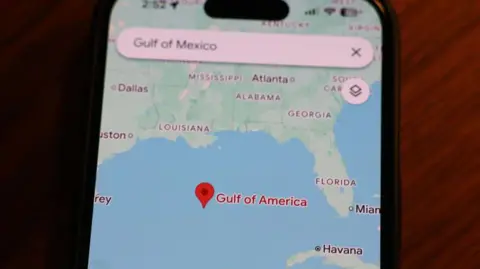

On his first day back in office, he signed an order renaming the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America. Denali, the indigenous name for the famed Alaskan peak, will revert back to Mount McKinley, a reference to the assassinated 19th century president.

Fort Bragg, which was named for a Confederate general until the military changed it to Fort Liberty, will again bear its original name – but this time attributed to a far less controversial soldier from World War Two.

Trump is not the first US president to rename a monument. It was Barack Obama, a Democrat, who renamed Mount McKinley to its Native American name, Denali, after years of lobbying from Alaskans.

George W Bush, a Republican, renamed the Caribbean National Forest in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico to the El Yunque National Forest in 2007, to reflect the US territory’s heritage.

And after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 sparked a national reckoning on race, Congress initiated a process to rename US military bases named after Confederate figures. In 2023, during Joe Biden’s presidency, the Department of Defense renamed nine US military bases, including Fort Bragg.

At the heart of these decisions is a desire to portray America, and its values, in a particular light.

“The act of naming is a way that presidents can reshape their vision of the nation,” said Allison Prasch, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies political rhetoric.

Trump’s choices in his second term send a clear message about his priorities too, she said.

“It is elevating a very nationalist, imperialist vision of the United States,” Ms Prasch said.

Some of Trump’s name choices are callbacks to America’s expansionist age, when the prevailing ideology said that America had a God-given mission to expand from shore to shore.

Part of President William McKinley’s legacy was his role in annexing Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines and Hawaii. In changing Denali’s name, Trump said he wanted to honour McKinley because he “made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent”.

It’s an ideology that seems to inform Trump today too, as he has also floated the idea of retaking the Panama Canal, which had once been under US control, buying Greenland and annexing Canada to become the “51st state”.

Meanwhile, renaming Fort Bragg is the latest in an ongoing debate over the legacy of the Confederacy – the coalition of southern states that seceded from the US over the issue of slavery and triggered the Civil War.

During Trump’s first administration, amid a national reckoning over racial injustice, Congress required the Pentagon to rename facilities named after Confederates and banned future military installations from being named after them.

The move rankled Trump then, who tried to veto the measure and declared that “our history as the Greatest Nation in the World will not be tampered with!” Congress overrode him with bipartisan support.

But historian Connor Williams, who served on the renaming committee that had recommended the name Bragg be removed in 2021, said that honouring the Confederacy is misguided.

“What makes Confederates such bad topics for commemoration is that they have very little to redeem them,” Williams said. “They committed treason against the United States.”

“What we commemorate, what we celebrate, what public displays we make, where we place wreathes – the president does have that ability to signal what he thinks is important,” he added.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2023, the Biden administration changed Fort Bragg, named after Confederate general Braxton Bragg, to Fort Liberty.

“We seized this opportunity to make ourselves better and to seek excellence,” Lt. Gen. Christopher Donahue said at the renaming ceremony. “That is what we always have done and always will do.”

However, the name change prompted mixed feelings among lawmakers, former military personnel who spent time there, and the local community.

“I understand the reasoning behind the change, and I have to accept it because it’s what the elected leadership has determined is in the best interest,” Cumberland County Commissioner Jimmy Keefe said at the time according to local media. “But I hate that so many people who have had positive experiences at Fort Bragg, who have had children born there, weddings there, that they will no longer have that tether of Fort Bragg in the name.”

This week, Trump’s new Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth, restored the base’s name to Fort Bragg. But this time, he said the base will be named after Private First Class Roland Bragg, who fought in World War II, rather than a Confederate general.

“That’s right,” Hegseth said. “Bragg is back.”

Republican lawmakers representing the base expressed enthusiasm about the change.

“Renaming Fort Bragg for Pfc. Roland L. Bragg, who earned the Silver Star and Purple Heart in WWII, was always the right decision,” North Carolina Senator Ted Budd wrote on Facebook.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut nationally, many of Trump’s name changes have proved controversial. A Marquette University poll suggested that 71% of US adults did not support changing the Gulf of Mexico’s name, and just 29% supported it.

Some of the changes have sparked debates about whose vision of American history should officially stand.

A poll by Alaska Survey Research suggested 47% of Alaska’s Trump’s voters favoured the name change. But overall, Alaskans opposed the name change by a two-to-one margin, the Juneau Express reported.

Democrats and Republicans in Alaska’s legislature banded together to pass a resolution urging Trump not to change Denali’s name.

“To officially change the name would not only dishonor those who have fought to protect Denali’s legacy but also dismiss the voices of the Native communities whose roots are intertwined with this land,” said Alaska Representative Maxine Dibert, a Democrat and a member of the indigenous Koyukon Athabascan community.

Time will tell whether Trump’s symbolic name changes endure. But the arguments about them shows no signs of abating.

This week, the White House blocked an Associated Press reporter from the Oval Office this week because the wire service kept Gulf of Mexico in its popular style guide. AP executive editor Julie Pace called the decision “alarming” and said it violated the constitution’s free speech rights.

Meanwhile, Google – which now uses the name Gulf of America on its maps for US users – has begun deleting negative reviews of the name change.

Renaming the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America might be a land (or water) grab on paper only, but its symbolism is undeniable, said Ms Prasch, the professor of political rhetoric at the University of Wisconsin.

And it goes beyond geography to strike a chord about how the country views itself – and its history.

“I actually think that this is much more than renaming a body of water on a map,” she said. “It is a fundamentally rhetorical decision about how we think about the story of the nation.”