“These are all harmless drugs. All athletes take them. It’s really nothing special.”

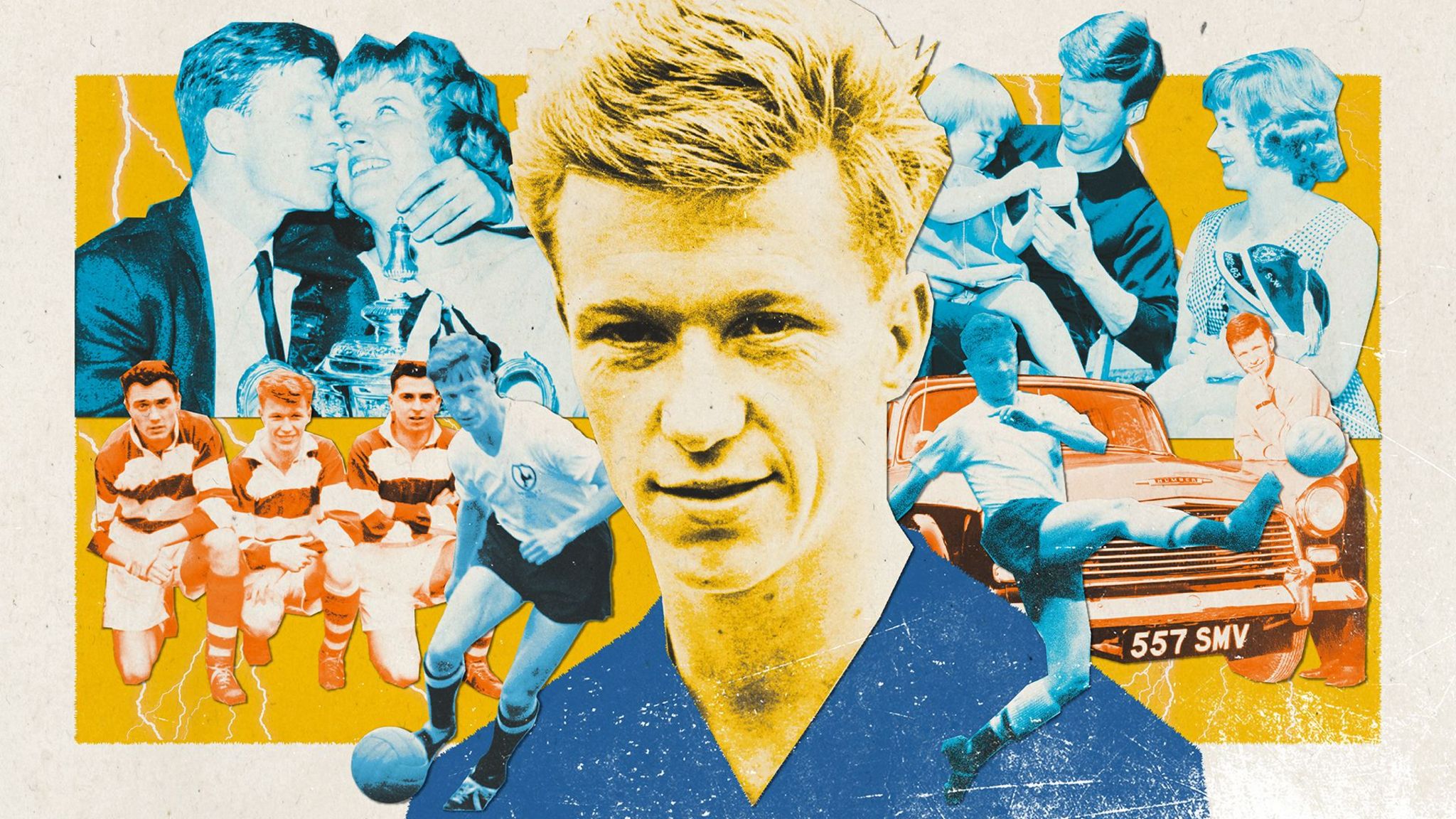

That was what German heptathlete Birgit Dressel, who finished ninth in the 1984 Olympic Games, once told her mother.

Sadly, those words couldn’t have been further from the truth. On 8 April 1987, after taking medication to help with a bad back, Dressel’s body went into allergic-toxic shock, leading to rapid organ failure.

After two days of agony in Mainz hospital, she died at the age of 26.

Her autopsy revealed traces of more than 100 drugs in her system, including anabolic steroids that she had been taking for years, while her medical history showed she had been injected with at least 40 different substances throughout her career, with one practitioner alone administering 400 injections.

During her final years, she became heavily reliant on prescription drugs to compete and live pain-free. Her tortuous training regime had pushed her body to the brink, and by the time of her death, she was experiencing hip pain, lateral bending of the spinal column, damage to the discs and fusion of the spinal vertebrae, displacement of the pelvis, degeneration of both kneecaps and sunken arches in her feet.

To combat the pain, she was reportedly taking nine pills a day, as well as additional drugs administered by three separate doctors.

Dressel’s demise was a harrowing example of how far humans will go to keep up, but her story had much broader implications.

After the reunification of Germany in 1990, a treasure trove of documents held by the then-defunct East German secret police, the Stasi, revealed what many had suspected for decades: East Germany had conducted a state-sponsored, systematic doping operation that led to spectacular sporting success.

As the sordid details were gradually revealed, Western European nations appeared vindicated.

Allegations of East Germany doping, along with other Soviet satellite states, had increased dramatically throughout the 1980s. Here was confirmation the other side had been cheating all along.

However, the narrative was not quite so simple. The division between ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ athletes was not as well-defined as the line that had cut Germany in half for nearly 50 years.

Dressel, born in Bremen and living in Mainz, was not from East Germany but from the West.

While they would take decades to emerge, West German sport had its own secrets.

“From the 1970s onwards, East Germany began winning a lot of medals. West German politicians started worrying about it and spreading the message that West German athletes needed to win medals too,” says Letizia Paoli, who chaired the 2009 committee investigating West German doping activity at the University of Freiburg.

“They couldn’t afford to look worse than the East. Medals were seen as an indicator of political and economic success.”

The East German doping system was comprehensive, systematic and all-encompassing. Stasi files revealed that an initially amateurish doping programme was transformed in 1974 by an innocuous-sounding piece of policy called State Research Plan 14.25. It mandated doping across all sports with the potential to deliver Olympic glory.

Thousands of athletes, some as young as 12, were shovelled through a programme where cheating was a prerequisite.

“The training regime was really tough. We trained three times a day, and when we weren’t training we did physiotherapy, sauna and yoga to recover. We were like well-bred horses waiting to race,” says Ines Geipel, a former East German athlete and author of a book, Behind The Wall, which details her experience in Cold War East Germany.

“As young people, sport was the only way for us to see the world – to get out.

“We were given various tablets in silver foil, but there was no information about them, just that they were good to take because we sweated so much while competing.”

Thanks to recovered documents, Geipel now knows she was primarily being given an anabolic steroid called oral turinabol.

Refusals or questioning led to the withdrawal of athletic sponsorship and a black mark against your name in Stasi files. That, in turn, could affect your chances of gaining employment, housing or benefits.

Geipel felt the full weight of the Stasi when officials uncovered her plans to defect and remain in Los Angeles after the 1984 Olympics to be with a Mexican athlete she had fallen in love with.

After returning to East Germany, the Stasi turned the screw, she was expelled from sport and, for many of her compatriots, became a social pariah.

“If you escaped, you were seen as a traitor,” said Geipel.

“Firstly, they wanted to find a man in the GDR [East Germany] who looked like the Mexican I’d fallen in love with.

“They thought if I met a man who looked like the Mexican, then everything would be good again. There wasn’t such a man.

“Then they tried to force me to commit to the Stasi. But I didn’t do it.

“The last stage, when they didn’t see any other option, was to operate on me and cut through my stomach.

“It’s all in the files… they cut the stomach in such a way, through all the muscles and everything so that I couldn’t run any more and didn’t have a way of getting to the rest of the world any more.”

In August 1989, she fled to the West via Hungary after crawling across the heavily-defended border.

It is possible to pick up the threads of Germany’s recent doping past and follow them back decades. Plenty lead to the Western side of the Cold War.

The day before the 2006 Tour de France, a doping scandal exploded. German rider Jan Ullrich, the 1997 Tour winner and one of that year’s favourites, was sitting on a bus on the way to a press conference when he received the news that his world was about to come down around him.

Operation Puerto, an investigation by Spanish police into doping in sport, had connected him to illegal blood transfusion.

The investigation’s details were scandalous: Manolo Saiz, the directeur sportif of the Liberty Seguros–Wurth team, was arrested with a briefcase of cash in Madrid. The Spaniard was never charged, but neither did he ever return to the top level of professional cycling.

Elsewhere a fridge filled with 186 blood bags, labelled with codenames belonging to athletes, was discovered at doctor Eufemiano Fuentes’ clinic, along with complex machines to manipulate and transfuse blood.

Investigations into his German-based T Mobile team later uncovered more than a decade’s worth of doping starting in the early 1990s, when it was known as Telekom.

Two team doctors, Andreas Schmid and Lothar Heinrich, admitted their involvement in long-term doping.

“I made available to cyclists, upon request, drug substances, especially EPO [erythropoietin, a hormone that causes the body to make more red blood cells],” said Schmid, claiming in his defence that he had never doped an unwitting athlete.

Both men came from one university department: the University Medical Center Freiberg, in south west Germany, just 20 miles from the French border.

The University of Freiberg responded by forming an independent committee to look into historic doping allegations.

The first commission was quickly dissolved due to health reasons, while Paoli, an Italian criminologist, was asked to chair the second and head a six-strong team of investigators.

She accepted, but her and her team’s relationship with the university soon deteriorated.

All six of the investigators resigned in protest at the lack of cooperation from the university and its departments, but ultimately did publish an independent report.

It painted a damning picture of decades of doping by medics based at Freiburg.

Two men were cited as key players: professors Joseph Keul and Armin Klumper.

From the 1960s onwards, Keul, who died in 2000, was the superstar physician in Germany, working with scores of top-level athletes and acting for more than 20 years as head physician of the German Olympic team.

Klumper joined Freiburg in the mid-1960s, initially as a medical assistant, before becoming head of sports traumatology.

“Unlike in East Germany, where it was a top-down doping system, in the West, much of it was outsourced to Freiburg,” says Paoli.

According to sources seen by the commission, as much as 90% of West German track and field athletes during the 1970s and 1980s passed through Freiburg – though how many doped may never be known. What’s clear is that Keul and Klumper played vital roles in West Germany’s and then Germany’s sporting successes.

“The athletes loved Klumper. He was excellent with his diagnostics and would go to the track and field to spend a lot of time with them, while Keul was more hands-off,” says Paoli.

Evidence of Klumper’s involvement in doping is staggering. His infamous ‘Klumper cocktails’ were referenced multiple times during interviews with ex-athletes.

“These were mixtures of off-label medicines, prescription medicines, doping products and natural remedies that were supposedly tailored to individual athletes’ needs,” says Paoli.

One such athlete was Dressel, who visited Klumper regularly for treatment. Her last visit to Freiburg came on the 24 February 1987 – less than three months before her death – where he reportedly gave her a cocktail containing 15 substances.

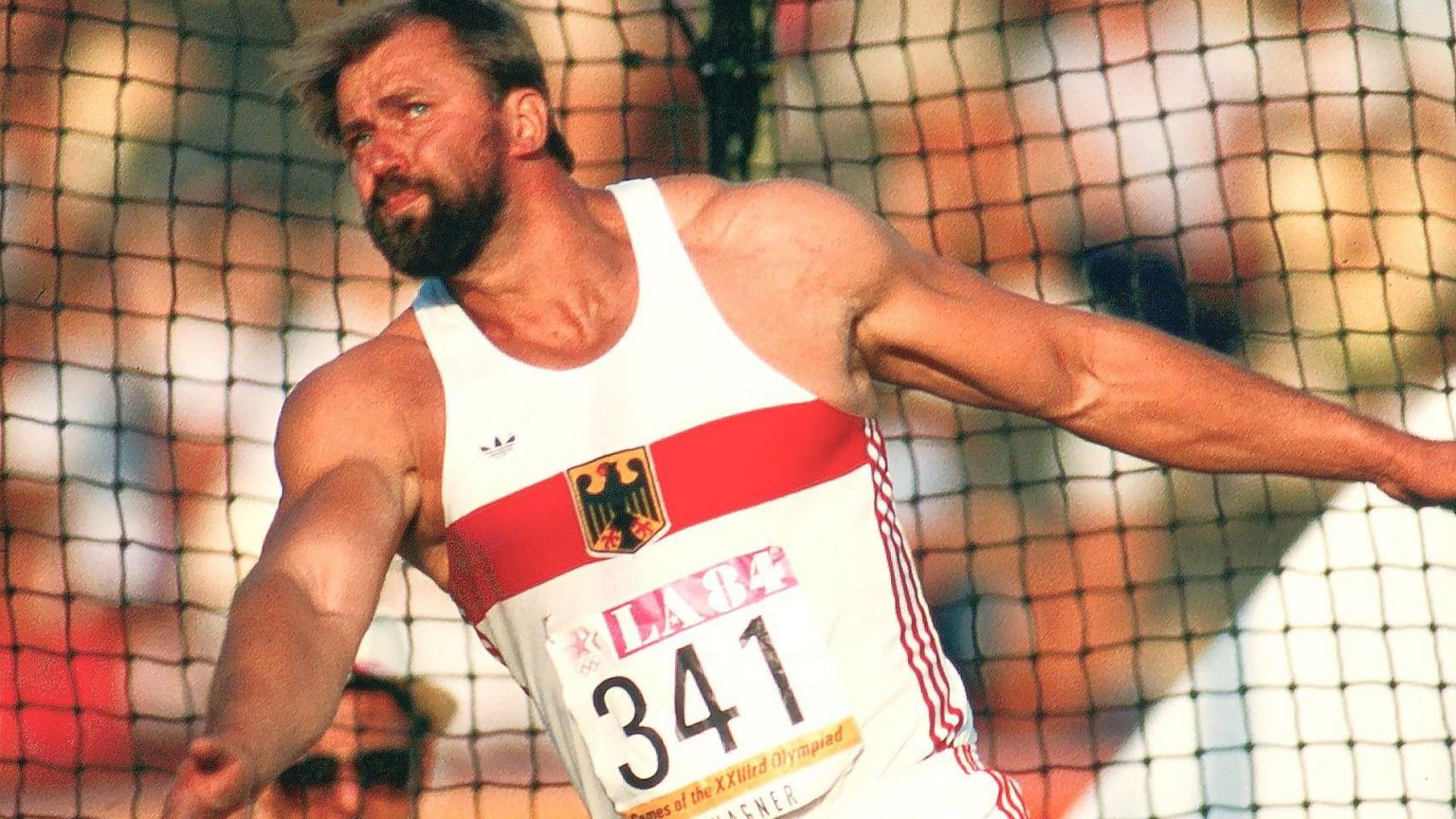

By the late 1980s, numerous West German sporting figures, including discus thrower Alwin Wagner and sprinter Manfred Ommer, were openly linking Klumper, who died in 2019, with historic doping. Yet he also had his supporters.

Even as his name began to sink under further allegations in 1997, a passionate defence was published in a national newspaper, signed by some major names in German sport at the time, including gymnast Eberhard Gienger, decathlete Jurgen Hingsen and footballer Wolfgang Overath.

Gienger subsequently admitted in 2006 that he had taken anabolic steroids during his career, saying he doped to aid his recovery after an operation and that Klumper “prescribed very generously”.

Hingsen insisted in 2016 that Klumper and Keul had never offered him anything illicit. Overath has since described any suggestion of doping during his time in elite sport as ‘absurd’.

Olympic medal-winning hammer thrower Uwe Beyer presented a prescription for steroids bearing Keul’s name, but, overall, direct evidence linking Klumper’s colleague with doping was less widespread.

Keul instead worked to undermine the growing evidence of the health risks of drug misuse and the anti-doping system designed to catch cheats.

In 1976, he gave an interview explaining how he justified his stance to himself and others.

“Where is it written that we should prevent harm?” Keul said to German broadcaster ZDF.

“That is a general medical task, but it has nothing to do with sports medicine.”

For him, healthy sportspeople gambling on performance enhancement was a separate branch of medicine, one where the usual considerations did not apply.

In 1992, with public funds drying up after the end of the Cold War, Keul began taking large amounts from external sources, including Deutsche Telekom’s cycling team, which later became T-Mobile.

The narrative of a virtuous West Germany emerging victorious from sport’s Cold War was dented when T-Mobile and Keul’s Freiburg colleagues were caught up in the Tour de France doping scandal in 2006.

In August 2013, it was fatally shattered.

A report commissioned by the German Ministry of Sport and carried out by researchers at Humboldt University in Berlin and the University of Munster – Leaks from Doping in Germany from 1950 to Today – appeared in various German newspapers.

The report was heavily redacted because of legal and privacy concerns, but was clear enough in its claim that doping was widespread on both sides of the Cold War divide and had continued after reunification.

The revelations on West German doping landed like a bombshell, with the reverberations travelling around the world.

The report alleged that West Germany’s shock comeback win over Hungary in the 1954 World Cup final – a game often called ‘The Miracle of Bern’ – had been powered by pervitin, an energy-boosting methamphetamine.

The drug had been studied in depth for its doping qualities at Freiburg during the 1950s.

Questions were also raised over West Germany’s 1966 World Cup, in which they reached the final but lost to England 4-2.

The report revealed that a letter from Fifa official Mihailo Andrejevic informed the president of the German Athletics Association, Max Danz, that “fine traces” of ephedrine – a central nervous system stimulant – were found in three players of the German national team.

No action was taken and some have speculated that the players may have consumed the ephedrine in a cold medicine.

By the time of the 1972 and 1976 Olympics, in Munich and Montreal respectively, organised doping was common among West Germany’s elite athletes, the report added.

While most of Germany’s sports federations agreed to take part and share documentation, according to the report, it was notable that the country’s athletic association refused to hand over the minutes of its presidential meetings, while “a former president of the federation was unwilling to allow access to doping-related documents in his possession”.

The report also states that the German Football Association only offered the researchers access under ultimately unacceptable conditions, while the security services refused access to potential doping-related documents from both West and East Germany.

Over a decade later, the initial report, even with redactions, is only available as a physical copy by request to the German government.

The Federal Institute for Sports Science (BISp) said the 804-page initial report did not “meet the requirements of good scientific work in form and content” and requested that it was revised.

A later, 43-page version has been made available more publicly.

The University of Freiberg told BBC Sport that it is “committed to the consistent, unreserved and transparent clarification of the past surrounding Freiburg sports medicine” and described the resignation of Paoli and her team of investigators and their failure to deliver a final report in conjunction with it as “very regrettable”.

The university has made some parts of the team’s provisional work available online.

Germany announced in July that it intends to bid to host the 2040 Olympic and Paralympic Games. If successful, the event would mark 50 years since reunification.

But, like the future, the country’s past is contested.

The Cold War had its victor, and victors often have the freedom to mould history and storylines as they see fit. Yet West Germany’s secrets have, at least partially, emerged to change the script.

East Germany doped its athletes on a chillingly industrial level that saw thousands drugged without clear consent to gain a sporting upper hand – but the situation in the West was far less opaque.

Those in West Germany were afforded freedom beyond the wildest dreams of East Germans, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that many chose exactly the same methods as the enemy.

For some, in the battle for Cold War medals, anything to gain an advantage was fair game.