Suhnwook Lee / BBC Korean

Suhnwook Lee / BBC KoreanAt first glance, Dunpo Elementary is no different from the thousands of elementary schools dotted across South Korea.

But look just beneath the surface and the differences are stark.

For one thing, most of the students in this school in Asan, an industrial city near the capital Seoul, may look ethnically Korean, but cannot speak the language.

“If I don’t translate into Russian for them, the other kids won’t understand any of the lessons,” says 11-year-old Kim Yana.

Yana speaks the best Korean in her class – but she and most of her 22 classmates are native Russian speakers.

Nearly 80% of the pupils at Dunpo are categorised as “multicultural students”, meaning they are either foreigners or have a parent who is not a Korean citizen.

And while the school says it is difficult to know exactly what these students’ nationalities are, most of them are believed to be Koryoins: ethnic Koreans typically hailing from countries in Central Asia.

Amid a plummeting birth rate and associated labour shortages, South Korea is touting the settlement of Koryoins and other ethnic Koreans as a possible solution to the nation’s population crisis. But discrimination, marginalisation, and the lack of a proper settlement programme are making it hard for many of them to integrate.

Suhnwook Lee / BBC Korean

Suhnwook Lee / BBC KoreanEssential workers

Koryoins are descendants of ethnic Koreans who migrated to the far east of the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries – before many were forcibly transferred to Central Asia in the 1930s as part of Stalin’s “frontier-cleansing” policy.

They lived in former Soviet states such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and, over the generations, assimilated into those cultures and stopped speaking Korean, which was forbidden.

South Korea started granting residency to Koryoins as well as ethnic Koreans in China after a landmark ruling by the country’s constitutional court in 2001. But the number of Koryoin migrants began growing rapidly from 2014 when they were allowed to bring their families into the country as well.

Last year, about 760,000 ethnic Koreans from China and Russian-speaking countries were living in South Korea, making up about 30% of the country’s foreign population. Many have settled in cities like Asan, which have more factories and therefore greater job opportunities.

Ni Denis, who migrated to South Korea from Kazakhstan in 2018, is one of them.

“These days, I don’t see Koreans in the factory [where I work],” he says. “They think the job’s difficult, so they leave quickly. More than 80% of the people I work with are Koryoins.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt isn’t only Koryoins, however, who are benefitting from the immigration boost. The influx of ethnic Koreans from abroad is also helping to address a severe labour shortage in a country whose population continues to shrink.

South Korea has the world’s lowest fertility rate, which keeps dropping year on year. In 2023, the birth rate was 0.72 – far behind the 2.1 required to maintain a stable population in the absence of immigration.

Estimates suggest that if this trend continues, South Korea’s population could halve by the year 2100.

The country will need 894,000 more workers, especially in the service industry, to “achieve long-term economic growth projections” over the next decade, according to South Korea’s Ministry of Employment and Labour.

Workers from overseas are helping to bridge the gap.

“While the overseas Korean visa is often perceived as a form of support for ethnic Koreans, it has been primarily serving to provide stable labour for manufacturing,” says Choi Seori, a researcher at the Migration Research and Training Centre.

Mr Lee, a recruiter in Asan who asked to be identified only by his surname, highlighted the workforce’s dependence on immigration another way.

“Without Koryoins,” he said. “these factories wouldn’t run.”

Segregation at school and beyond

Yet while immigration may be one solution to the country’s workforce problem, it comes with its own set of issues in this ethnically homogenous society.

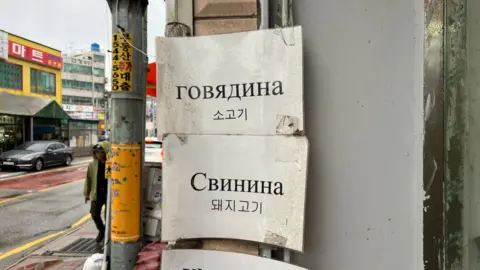

Language is one of them.

“Korean kids only play with Koreans and Russian kids only play with Russians because they can’t communicate,” says 12-year-old student Kim Bobby.

In an attempt to overcome the language barrier, Dunpo Elementary School runs a two-hour Korean class for foreign students every day. Even so, teacher Kim Eun-ju is worried that many children “hardly understand the lessons” as they move up grades.

Academic competition in South Korea is notoriously rife and the school is losing local students, as parents worry their children’s education is being affected because lessons have to be conducted at a slower pace for Koryoins.

The high school enrolment rate for multicultural students is already slightly lower than for locals, according to an official national survey conducted in 2021. Park Min-jung, a researcher at the Migration Research and Training Centre, worries that more Koryoin students will drop out of school if they don’t get the support they need.

Ni Denis

Ni DenisAnd language is not the only point of difference.

Mr Ni says he has noticed that many of his Korean neighbours have moved out of their building.

“Koreans seem to dislike having Koryoins as neighbours,” he says with an awkward laugh. “Sometimes Koreans ask us why we don’t smile at them. It’s just the way we are; it’s not that we’re angry.”

He says there have been disputes between children in his neighbourhood, and he has heard of cases where Koryoin children have been “rough” during arguments. “After that, Korean parents tell their kids not to play with Koryoin kids. I think that’s how segregation happens.”

“I am concerned about how Korea will be able to accept other immigrants,” says Seong Dong-gi, an expert of Koryoin at Inha University, explaining that there is already “significant resistance” to the influx of ethnic Koreans who “do not look different”.

The population crisis should be a “catalyst for society to look at immigration differently”, says Ms Choi. “It’s time to think about how to integrate them”.

Suhnwook Lee / BBC Korean

Suhnwook Lee / BBC KoreanIn 2023 there were roughly 2.5 million foreigners living in South Korea, which is also a popular destination for migrant workers from places such as Nepal, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Most of them work in manual jobs, with only 13% in professional roles.

“There is no clear plan for immigration at the national government level,” says Lee Chang-won, the director of the Migration Research and Training Centre. “Solving the country’s population problem with foreigners has been an afterthought.”

Mr Lee adds that the current immigration policy is “heavily weighted towards low-skilled workers”, leading to a “common view” that foreigners only work in South Korea for a while and then leave. As a result, he says, there has been little discussion about long-term settlement for all immigrants.

According to current laws, the government is only required to provide support with things like vocational training for foreigners who marry locals. The same rights, however, are not extended to families entirely made up of foreigners.

Analysts say a new law for these families is urgently needed.

An Asan official, who requested anonymity, says it is difficult to secure funding for more supporting facilities for Koryoin families because there is no legal requirement to do so.

But despite these challenges, Mr Ni says he has not regretted the decision to move to South Korea. He still gets a better living environment and higher wages here.

“For my children, this is home,” he says. “When we visited Kazakhstan, they asked: ‘Why are we here? We want to go back to Korea.’”