BBC

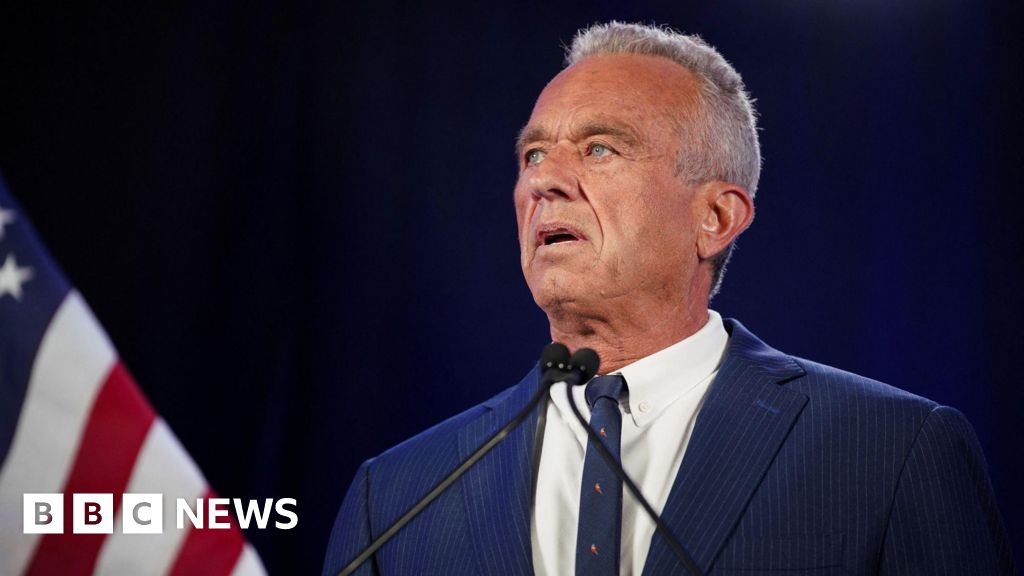

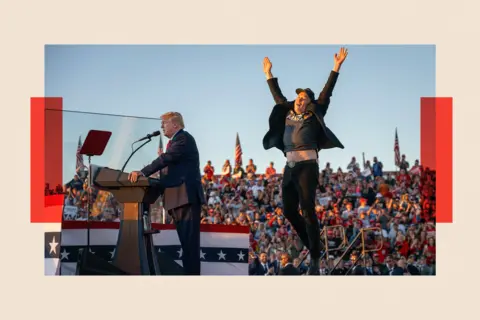

BBC“It’s insane! We’re heading for a general election. The country feels broken. Our economy is stagnant… But most German news outlets just seem obsessed with Trump, Trump, Trump!”

Iris Mühler, a teacher in engineering in north-east Germany is one of a number of voters I’ve been talking to ahead of February snap elections. She isn’t alone in her perception.

Despite facing a whole raft of its own domestic difficulties – not least in leading EU countries, Germany and France – Europe has been very Trump-focused since he won the US presidential election in November.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe continent had a bumpy ride last time he was in the White House. Many fear Trump 2.0 could be a lot worse. And Europe’s traditional powers are already struggling with their own problems.

France and Germany are mired in political and economic woes, the EU as a whole lags behind China and the US in terms of competitiveness, while in the UK, public services are in a woeful state.

So: is the continent prepared for Donald Trump or has it been caught napping at the wheel (again)?

A businessman who dismisses alliances

When it comes to trade and defence, Trump acts more like a transactional businessman than a US statesman who prizes transatlantic alliances dating back to World War Two.

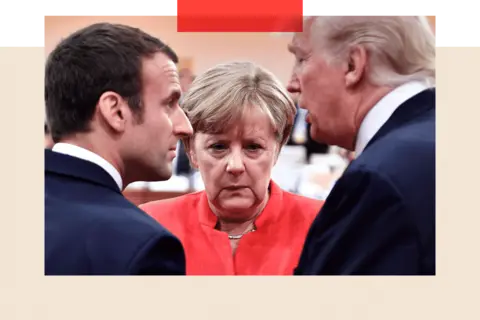

“He simply doesn’t believe in win-win partnerships,” the former German Chancellor Angela Merkel told me. She experienced Trump last time he was in office and concluded he views the world through the prism of winners and losers.

He’s convinced that Europe has taken advantage of the US for years and that’s got to stop.

Leaders in Europe have watched open-mouthed these last weeks since Trump won the US presidential election, for the second time. He’s chosen to publicly lambast allies in Europe and Canada, rather than focus his ire on those he recognises as a strategic threat, like China.

Trump dangles the possibility of abandoning Nato – the transatlantic military alliance that Europe has relied on for its security for decades. He has said he’d “encourage” Russia to do “whatever the hell they want” with European allies if they “don’t pay” their way more and boost their defence spending.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen it comes to trade, Trump is clearly as livid with the EU now as he was during his first term in office. The bloc sells far more to the United States than it imports from the US. In January 2022, the trade surplus was €15.4 billion (£13 billion).

Donald Trump’s answer? He says he’ll impose blanket tariffs on all foreign imports of 10-20%, with even higher tariffs on certain goods like cars.

That’s a disaster scenario for Germany, which relies on exports and the automobile industry in particular. Its economy is already spluttering – last year it shrunk by 0.2%.

As the biggest economy in the eurozone, financial difficulties in Germany risk affecting the currency as a whole.

Germany is ‘top of Trump’s hit list’

Merkel has said that when he was president last time, Trump appeared to have it in for Germany.

Ian Bond, the deputy director for the Centre for European Reform, believes the country will remain “top of Trump’s (European) hit list.”

“What he said in the past is things like, he doesn’t want to see any Mercedes-Benz on the streets of New York. Now, this is kind of nuts, because, actually, most of the Mercedes-Benz that you see on the streets of New York are made in Alabama, where Mercedes has a big plant.

Getty Images

Getty Images“He has often been more hostile to Germany than any other country in Europe. It might be slightly easier for Germany with a new and more conservative government (after the upcoming general election), but I wouldn’t be holding my breath.”

The UK hopes to avoid Trump tariffs as it doesn’t have such a trade imbalance with the US, but it may well get lashed by tail winds if it comes to an EU-US trade war.

How prepared Europe is, really

Trump’s bullish style can come as no surprise to allies after his first term in the White House. The real conundrum for Europe now is his unpredictability: How much is bluster and intimidation and how much is a promise of action?

Ian Lesser, vice president at the German Marshall Fund of the United States think tank, believes Trump’s tariff threats are real and that Europe is far from ready.

“They’re not prepared, no one really is. This very different approach to global trade upsets many cornerstones of the international economy, which has evolved over decades.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe European Commission claims to be ready for any number of moves by Trump when he returns to the White House. It is a huge trade power on the world stage. But Mr Lesser says the biggest impact on Europe could come if Trump launches an aggressive trade war against China. That could result in supply chain disruptions for Europe and Beijing dumping even more cheap products on European markets, to the detriment of local businesses.

“For Europe it’s double exposure: exposure to what America might do and then what China will do in response.”

Trade, defence and the Musk factor

What complicates things further is that trade and defence aren’t separate issues for Trump and his administration. He recently refused to rule out economic and/or military action against EU and Nato member Denmark if it didn’t hand over the autonomous territory Greenland to the US.

And Trump’s incoming vice president appeared, this autumn, to make US defence of Europe conditional on EU regulatory bodies stepping away from the social platform X.

JD Vance warned the US could pull its support for Nato if the EU continued a longstanding investigation into X, which is owned by Trump’s Golden Boy, Elon Musk.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRecently, Mr Musk also displayed a keenness for taking sides in European politics. He launched repeated online attacks against centre-left European leaders Sir Keir Starmer in the UK and outgoing German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. Musk posted on X that the extreme anti-migration AfD party was Germany’s only hope.

This shocked many in Europe but pollsters suggest Mr Musk’s controversial posts have little actual influence on European public opinion.

Trump and Mr Musk are widely distrusted in Europe, as clearly illustrated in a new poll commissioned by the European Council of Foreign Relations, entitled The EU and global public opinion after the US elections.

From ego flattering to flashing cash

In the end, different European leaders have different approaches to “Taming the Trump,” as insiders describe attempts. Some flatter his not-exactly-tiny ego.

French President Emmanuel Macron is the expert here. He was one of the first world leaders to congratulate Trump on social media after his re-election in November and he swiftly invited him to attend the glittering and dignitary-resplendent re-opening of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

When he was first in the White House, President Macron wowed Trump as guest of honour at the annual display of pomp and military might of Bastille Day in Paris.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK, meanwhile, knows Trump has a soft spot for Scotland, where his mother comes from, and for the British Royal Family. He visibly relished attending a state banquet with the now-late Queen Elizabeth II in 2019. He heaped praise on Prince William after sitting down with him this autumn.

Others in Europe favour flashing the cash.

European Central Bank (ECB) chief, Christine Lagarde, has advised Europe’s leaders to adopt a “cheque-book strategy” and negotiate with Trump rather than retaliate against his proposed tariffs.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, speaks of buying more (expensive) US liquified natural gas (LNG) as part of Europe’s effort to diversify its energy supplies. It has been weaning itself off a reliance on cheap Russian gas since the Kremlin launched its large-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Sources in the Commission also speak of possibly buying more US agricultural products and weapons.

Should Europe be more self-sufficient?

Macron, meanwhile, has long advocated what he calls “strategic autonomy” – essentially Europe learning to be more self-sufficient, in order to survive.

“Europe… can die and that depends entirely on our choices,” he said this spring.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCovid showed Europe how dependent it was on Chinese imports, like medicines. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine exposed Europe’s over-reliance on Russian energy.

Macron is now sounding the alarm about the US: “The United States of America has two priorities. The USA first, and that is legitimate, and the China issue, second. And the European issue is not a geopolitical priority for the coming years and decades.”

Trump’s return to the White House is making European leaders think about continental weaknesses.

The big question around defence

When it comes to defence, Trump’s insistence that Europe spend more is generally accepted (though how much more is a hot topic of debate). But where Trump talks in terms of increasing GDP spending, Europeans are discussing how to spend their defence budgets more wisely and in a more joined-up way to boost continental safety.

Emmanuel Macron wants an EU-wide industrial defence policy. He says the war in Ukraine illustrated that “our fragmentation is a weakness… We have sometimes discovered ourselves, as Europeans, that our guns were not of the same calibre, that our missiles did not match.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEurope frets that Trump will not want to continue being the main sponsor of military aid to Ukraine as was the case under the Biden administration.

Next month, EU leaders have invited the UK – one of Europe’s two big military powers – to an informal summit to discuss working together better on security and defence.

The EU’s defence chief and former Estonian prime minister, Kaja Kallas, believes European unity of purpose is needed. “We need to act in a united way. Then, we are strong. Then, we are also serious on the world stage.”

Weaker and more fractured? Europe today

There are analysts who say Europe is in a far weaker, more fractured state to deal with Trump 2.0 than it was in 2016 when he was first elected. I’d say the answer to that is yes. But also no.

Yes – as discussed, economic growth is sluggish and politics are volatile.

Populist nationalist eurosceptic parties are gaining strength in many European countries. Some, like Germany’s AfD, are soft on Moscow – while others like Italian PM Giorgia Meloni may be tempted to prioritise transatlantic ties with Trump rather than European unity.

But beware of looking back at Europe when Trump was first elected president through rose-tinted spectacles.

EPA

EPAFinancially, northern Europe was definitely doing better than it is now, but, in terms of unity, the continent was deeply divided on the back of the migrant crisis in 2015. Populist eurosceptic parties were also on the rise then and, following the Brexit vote in June 2016, there were widespread predictions the EU would soon lose other member countries and fall apart altogether.

Fast forward to 2025 and the EU has weathered Brexit, the Covid pandemic, the migration crisis and Trump’s first term in office – and countries very much pulled together after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

It was more of a stumbling, rather than sailing through these successive crises, but the EU is still standing and the wounds of Brexit, for example, have healed with time.

Post-Brexit UK is seen by the EU as a close ally that shares the same values in a world threatened by an ambitious China, an expansionist Russia and an unpredictable, bullish incoming US president.

Nato, meanwhile, though worried about Trump’s commitment to the alliance, has been boosted militarily and geostrategically by Sweden and Russian neighbour Finland becoming members following the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Maybe, just maybe, Trump will see fewer differences that frustrate and antagonise him about Europe this time round.

It’s a Europe that recognises the need to spend more on defence, as he demands; that is far warier of China, as he expects, and that is more right-leaning in its politics, as he prefers.

Is it a Europe whose leaders also stand up to Trump, despite threats and bluster, if they feel he crosses a line – be it over human rights, free speech or dallying with dictators?

The next chapter in relations between transatlantic frenemies waits to be written.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.