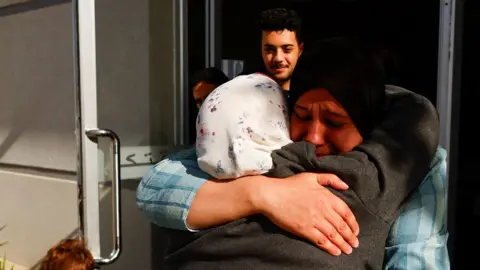

REUTERS/Ibraheem Abu Mustafa

REUTERS/Ibraheem Abu MustafaIt’s been 10 months since my family left Gaza but we continue to live with the loss, the pain, the impact of the war in all its excruciating detail.

This month – just before the anniversary of the beginning of the conflict – we saw the most harrowing eight hours we’ve experienced in that time.

We received a video message from my wife’s cousin in Gaza, saying: “The tanks are surrounding us and firing at us. These could be the last moments of our lives.

“Pray for us and do anything to save us.”

My wife collapsed, she even lost consciousness: her uncle, aunts and their families – 26 people in total- were all under attack.

Israeli raids and advances into cities and villages all over Gaza – targeting Hamas – have been common for most of this year now.

We didn’t hear anything from them for several hours. They were under bombardment the whole time. Then, finally, a voice note: “Four people have been injured. Your aunt Wafaa is bleeding, her condition is critical.”

I made countless calls, to the Red Cross, the Palestinian Red Crescent, anyone who could help.

After eight hours, the Israeli army finally allowed them to evacuate and move the wounded on foot.

But it was too late for Wafaa – she succumbed to her injuries shortly after reaching the hospital.

We still have so many relatives in Gaza. My father is there, living in a tent in the southern city of Khan Younis, which was bombed again this week.

I’m often overwhelmed by guilt when I call him from Istanbul, where I’ve fled to with my wife and two children.

There are so many people like me, in Turkey, in Egypt, and further afield around the world – the UK, the US, Europe – where we’ve had to go to find safety.

Not everyone can get out, only those with enough money to pay the high fees for passage elsewhere.

But in Egypt alone, more than 100,000 Gazans have crossed south into the country since November.

EPA

EPAThey’re not under immediate threat there from Israel’s bombs. But many are struggling to feed their families, provide education for their children, and just re-establish the basics of a normal life.

In an open-air, bustling café in Nasr City in Cairo, dozens of newly arrived refugees huddle in small groups, puffing on hookahs, sharing stories about their homeland.

They’re trying to alleviate the pangs of longing for those not currently with them. They cling to hope that the war will end soon, that they can return. But there’s a constant thrum of anxiety.

A loud traditional Palestinian song plays over the speakers – a hit by Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf, who won the Arab Idol competition a few years ago.

“Pass through Gaza and kiss its sand. Its people are brave and its men are strong.”

58-year-old Abu Anas Ayyad is among those sitting there, listening. In his past life he had been known as the “King of Gravel”, a successful businessman who had supplied building materials to constructions sites all over Gaza.

He and his family – including four children – escaped. But: “Every missile that hits a building in Gaza feels like a piece of my heart shattering.

“I still have family and friends there,” he says.

“All of this could have been avoided. But Hamas has a different opinion.”

He rues the Iran-backed group’s attack in Israel on 7 October 2023 and the consequences now.

“Despite my love for Gaza, I will not return if Hamas remains in power,” he says. He doesn’t want his children to be “used as pawns in a dangerous game played by reckless leaders for the sake of Iran.”

Sitting nearby is Mahmoud Al Khozondr, who before the war had run his family’s renowned hummus and falafel shop in Gaza. It’s an institution in the territory – known for its food and celebrity clientele. The late Palestinian president Yasser Arafat had been a frequent patron, often spotted at its tables.

Mahmoud shows me pictures of his former well-appointed family home on his phone. They now live in a cramped two-room apartment. His children can’t go to school.

“It’s a miserable life,” he says. “We lost everything back home. But we must rise again,” he says.

“We need food for our children, and assistance for our people still in Gaza.”

Living in exile in Egypt is not easy. The authorities have allowed Palestinians to stay temporarily, but they don’t grant official residency. They limit access to education and other key services.

REUTERS/Ibraheem Abu Mustafa

REUTERS/Ibraheem Abu MustafaMany Gazans try and send money back to support relatives still in Gaza – but remittance fees are steep and war merchants take a 30% cut.

“It’s heart-breaking to see profits being made from our loved ones’ suffering,” Mahmoud Saqr tells me.

He used to own an electronics store in Gaza. These days he has to take a bundle of cash to a shop in Cairo to transfer money to his sister.

“There’s no receipt, no proof—just a message hours later confirming they’ve received the money,” he tells me, describing the process.

“It’s risky, because we don’t know who is involved in this transaction but we have no choice.”

These are desperate times for everyone.

Over the past year in Turkey, I’ve tried in vain to create a peaceful living environment for my family.

But every time we go to a restaurant, my children reminisce about their favourite spots in Gaza, their large home, their games shop, their friends at the horse club, their classmates.

Some of those classmates have been killed in the Israeli air strikes, which continue.

But since October 7, time has stood still for us. We have yet to move on from that day.

We may have escaped physically, but our souls and hearts remained tethered to our loved ones in Gaza.