The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season is coming to an end and it has been an active one overall.

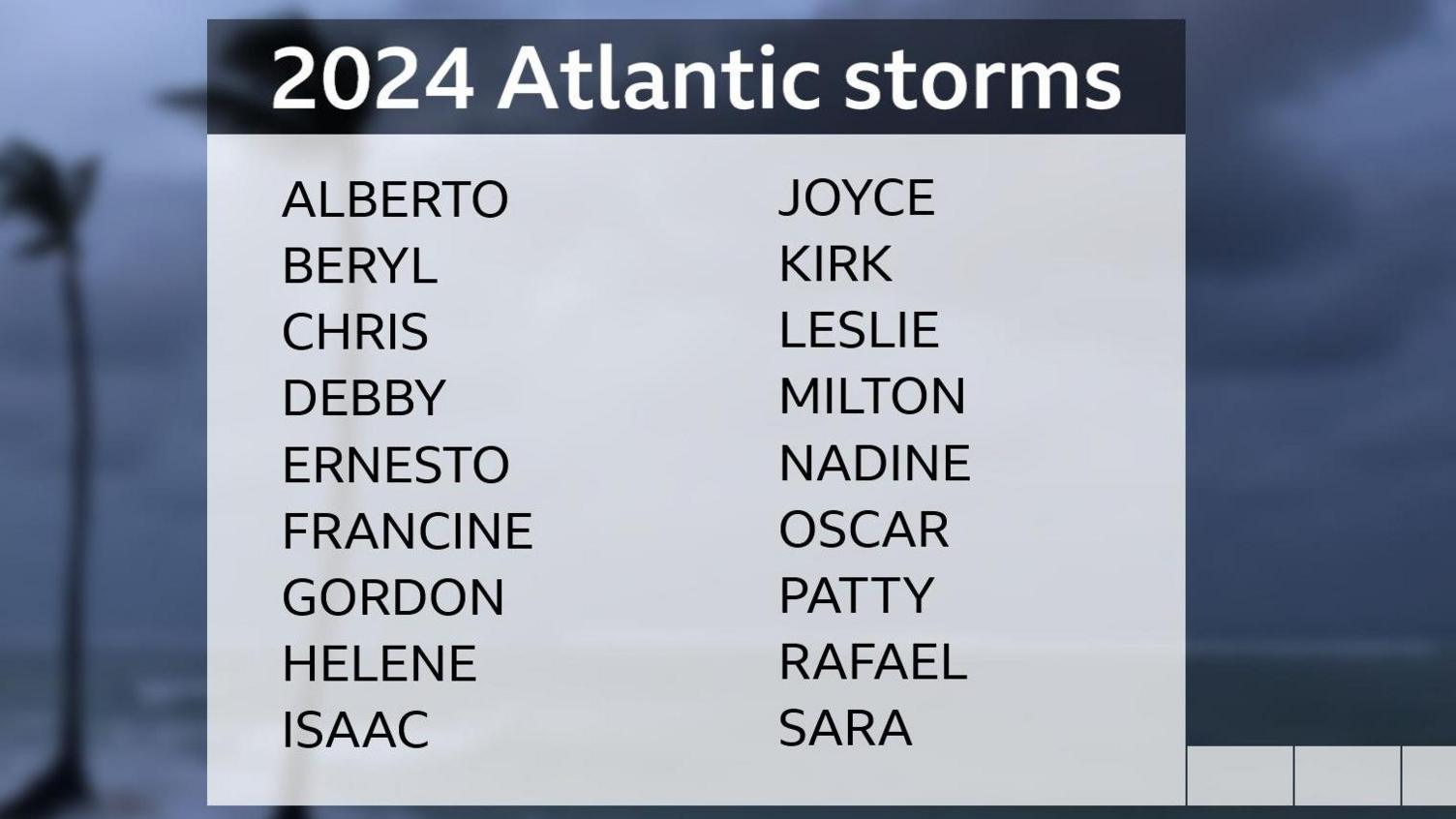

There have been 18 named tropical storms, with 11 of those reaching hurricane strength and five becoming major hurricanes – category three and above.

An average season would bring 14 storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

Some records have been equalled or broken but the active weather was not spread evenly across the season. In fact the middle of the season, normally the peak, was very quiet.

A lively start

Pre-season forecasts suggested this would be an above-average season – “extraordinary” according to some predictions.

There were early signs that it would live up to these expectations, with Hurricane Beryl becoming the Atlantic’s earliest category five hurricane on record on 2 July.

It caused widespread damage and a number of deaths across the Caribbean before hitting the coast of southern Texas, bringing flooding and power cuts here and in the neighbouring state of Louisiana.

But after Beryl dissipated, the Atlantic fell quiet.

-

-

11 October

-

A lull in proceedings

The hurricane season runs from 1 June to 30 November with activity typically reaching its peak in early September. But after Beryl in July there were only four named storms – and no major hurricanes – until Helene formed on 24 September.

This quiet spell was, on the face of it, something of a surprise.

Hurricanes are fuelled by warm oceans, and sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic were consistently above average.

The end of El Nino, which can put the brakes on hurricane development, was also expected to mean storms would form readily.

But the formation of hurricanes is a complex recipe requiring many ingredients.

It is thought that a shift in weather patterns in Africa – which brought rare rain to the Sahara – meant the clusters of thunderstorms that give birth to tropical systems emerged into the Atlantic further north than usual in an area less ripe for development. Large amounts of Saharan dust may also have suppressed activity.

But sea surface temperatures remained high – meaning the potential for powerful hurricanes remained.

The Atlantic roars back to life

This potential was realised in late September with the birth of Hurricane Helene. It intensified rapidly before making landfall on the Florida coast as a major category four storm.

Helene brought catastrophic flooding and widespread wind damage across large swathes of the south-east US, from Florida’s Gulf Coast to the southern Appalachians.

According to preliminary data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) it was the deadliest hurricane to affect the continental US since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, causing more than 150 deaths.

Helene was the first of six storms to develop in quick succession. Five of these became hurricanes of which four underwent rapid intensification, where sustained winds strengthen by at least 35mph (56km/h) in 24 hours.

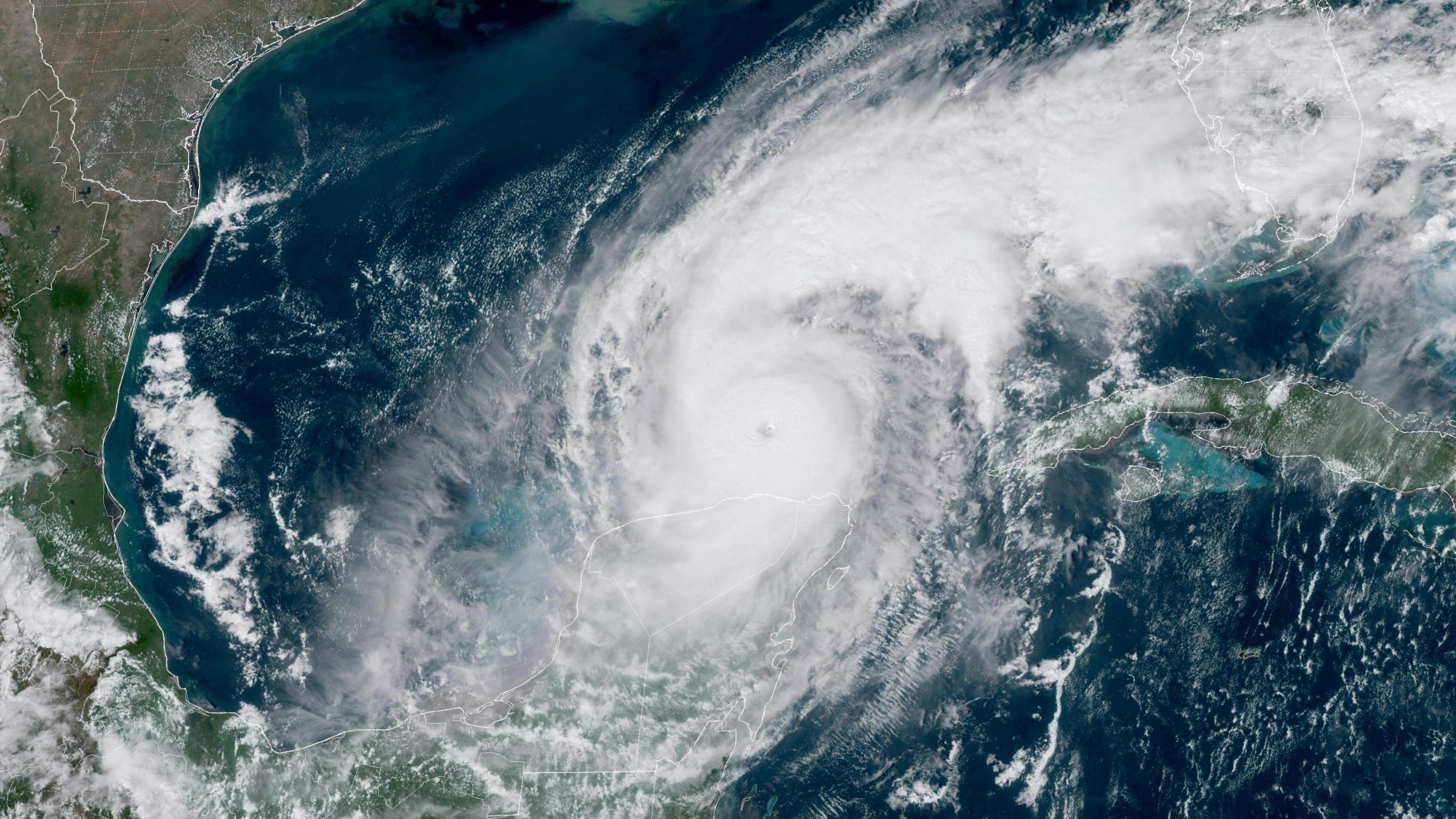

This culminated with Hurricane Milton, which formed in the Gulf of Mexico in early October and saw its wind speeds increase by a massive 90mph (145km/h) in 24 hours – one of the most extreme examples of rapid intensification on record.

It reached category five strength for a time, before weakening to a category three and making landfall on the west coast of Florida. It brought widespread impacts including a destructive storm surge and an outbreak of 46 tornadoes.

The final storm of the Atlantic season was Tropical Storm Sara. This storm did not strengthen into a hurricane – but it became slow-moving close to the coast of Central America, bringing widespread flooding. The north coast of Honduras saw more than 3ft (nearly 1m) of rain.

Is climate change to blame?

High sea temperatures are a key driver of tropical storms and hurricanes – these have been around 1C above the 1991-2020 average, according to BBC analysis of data from the European climate service.

This fits a pattern of warm oceans around the globe, fuelled by climate change.

Analysis by Climate Central has found that maximum wind speeds in every Atlantic hurricane in 2024 were higher because of climate change. In the case of Hurricane Milton, the winds were 23mph stronger as a result of human-induced global warming.

The very high sea temperatures that fuelled the storm were made 400 to 800 times more likely by climate change

Meanwhile a study by World Weather Attribution shows that climate change increased rainfall from Milton by 20-30%.

Globally, scientists say that tropical cyclones and hurricanes are unlikely to become more frequent overall. But those that do occur will intensify more rapidly and bring more rainfall – making them increasingly dangerous.

-

-

3 days ago

-