BBC

BBCThere is a young woman sheltering under a tree between two busy roads clutching a pile of documents to her chest.

These pieces of paper are more important to Bibi Nazdana than anything in the world: they are the divorce granted to her after a two-year court battle to free herself from life as a child bride.

They are the same papers a Taliban court has invalidated – a victim of the group’s hardline interpretation on Sharia (religious law) which has seen women effectively silenced in Afghanistan’s legal system.

Nazdana’s divorce is one of tens of thousands of court rulings revoked since the Taliban took control of the country three years ago this month.

It took just 10 days from them sweeping into the capital, Kabul, for the man she was promised to at seven to ask the courts to overturn the divorce ruling she had fought so hard for.

Hekmatullah had initially appeared to demand his wife when Nazdana was 15. It was eight years since her father had agreed to what is known as a ‘bad marriage’, which seeks to turn a family “enemy” into a “friend”.

She immediately approached the court – then operating under the US-backed Afghan government – for a separation, repeatedly telling them she could not marry the farmer, now in his 20s. It took two years, but finally a ruling was made in her favour: “The court congratulated me and said, ‘You are now separated and free to marry whomever you want.'”

But after Hekmatullah appealed the ruling in 2021, Nazdana was told she would not be allowed to plead her own case in person.

“At the court, the Taliban told me I shouldn’t return to court because it was against Sharia. They said my brother should represent me instead,” says Nazdana.

“They told us if we didn’t comply,” says Shams, Nazdana’s 28-year-old brother, “they would hand my sister over to him (Hekmatullah) by force.”

Her former husband, and now a newly signed up member of the Taliban, won the case. Shams’ attempts to explain to the court in their home province of Uruzgan that her life would be in danger fell on deaf ears.

The siblings decided they had been left with no choice but to flee.

When the Taliban returned to power three years ago, they promised to do away with the corruption of the past and deliver “justice” under Sharia, a version of Islamic law.

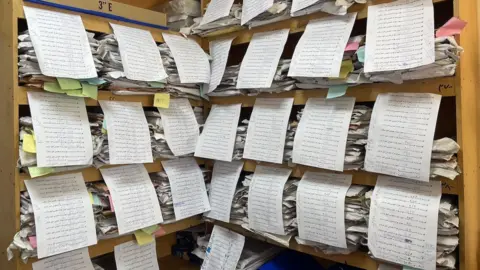

Since then, the Taliban say they have looked at some 355,000 cases.

Most were criminal cases – an estimated 40% are disputes over land and a further 30% are family issues including divorce, like Nazdana’s.

Nazdana’s divorce ruling was dug out after the BBC got exclusive access to the back offices of the Supreme Court in the capital, Kabul.

Abdulwahid Haqani – media officer for Afghanistan’s Supreme Court – confirms the ruling in favour of Hekmatullah, saying it was not valid because he “wasn’t present”.

“The previous corrupt administration’s decision to cancel Hekmatullah and Nazdana’s marriage was against the Sharia and rules of marriage,” he explains.

But the promises to reform the justice system have gone further than simply reopening settled cases.

The Taliban have also systematically removed all judges – both male and female – and replaced them with people who supported their hardline views.

Women were also declared unfit to participate in the judicial system.

“Women aren’t qualified or able to judge because in our Sharia principles the judiciary work requires people with high intelligence,” says Abdulrahim Rashid, director of foreign relations and communications at Taliban’s Supreme Court.

For the women who worked in the system, the loss is felt heavily – and not just for themselves.

Former Supreme Court judge Fawzia Amini – who fled the country after the Taliban returned – says there is little hope for women’s protections to improve under the law if there are no women in the courts.

“We played an important role,” she says. “For example, the Elimination of Violence against Women law in 2009 was one of our achievements. We also worked on the regulation of shelters for women, orphan guardianship and the anti-human trafficking law, to name a few.”

She also rubbishes the Taliban overturning previous rulings, like Nazdana’s.

“If a woman divorces her husband and the court documents are available as evidence then that’s final. Legal verdicts can’t change because a regime changes,” says Ms Amini.

“Our civil code is more than half a century old,” she adds. “It’s been practised since even before the Taliban were founded.

“All civil and penal codes, including those for divorce, have been adapted from the Quran.”

But the Taliban say Afghanistan’s former rulers simply weren’t Islamic enough.

Instead, they largely rely on Hanafi Fiqh (jurisprudence) religious law, which dates back to the 8th Century – albeit updated to “meet the current needs”, according to Abdulrahim Rashid.

“The former courts made decisions based on a penal and civil code. But now all decisions are based on Sharia [Islamic law],” he adds, proudly gesturing at the pile of cases they have already sorted through.

Ms Amini is less impressed by the plans for Afghanistan’s legal system going forward.

“I have a question for the Taliban. Did their parents marry based on these laws or based on the laws that their sons are going to write?” she asks.

Under the tree between two roads in an unnamed neighbouring country, none of this is any comfort to Nazdana.

Now just 20, she has been here for a year, clutching her divorce papers and hoping someone will help her.

“I have knocked on many doors asking for help, including the UN, but no-one has heard my voice,” she says.

“Where is the support? Don’t I deserve freedom as a woman?”